Phytic Acid: Everything You Need to Know

Phytic acid is a common antinutrient naturally occurring in many plant foods that people regularly consume.

As an antinutrient, phytic acid can prevent you from absorbing important nutrients while inhibiting the enzymes you need for digestion.

Read on to learn more about phytic acid, and what you can do to protect yourself from its possible adverse effects.

What Is Phytic Acid?

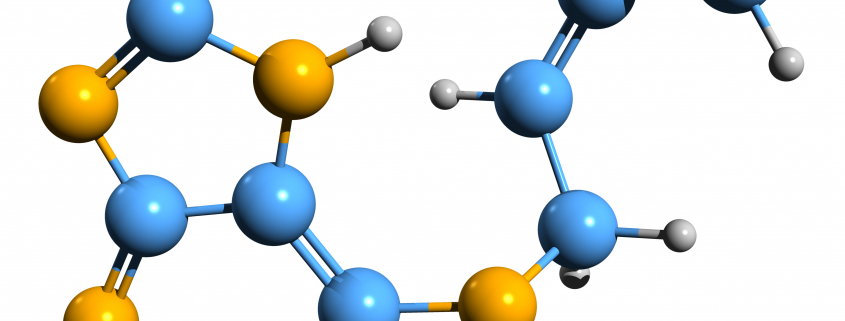

Phytic acid, also known as phytate, is a compound found in the seeds of plants. Plants use phytic acid to store phosphorus, which is vital for their growth and reproduction.

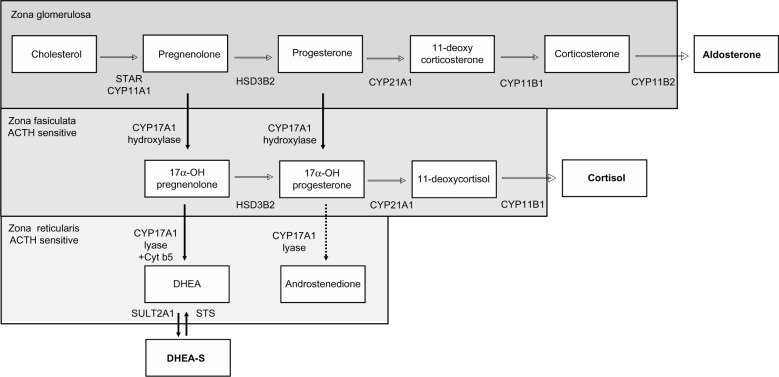

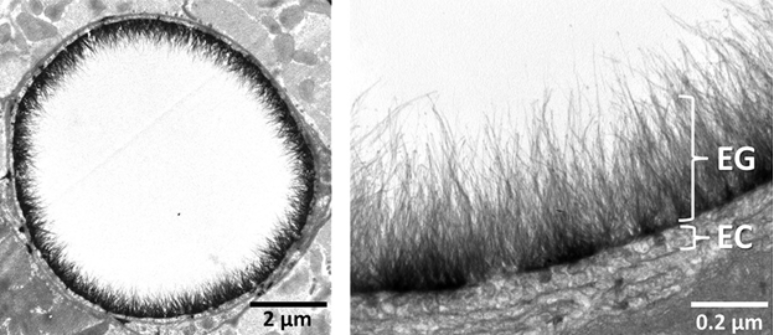

Six-sided phytic acid molecule with a phosphorus atom in each arm. Image from westonaprice.org

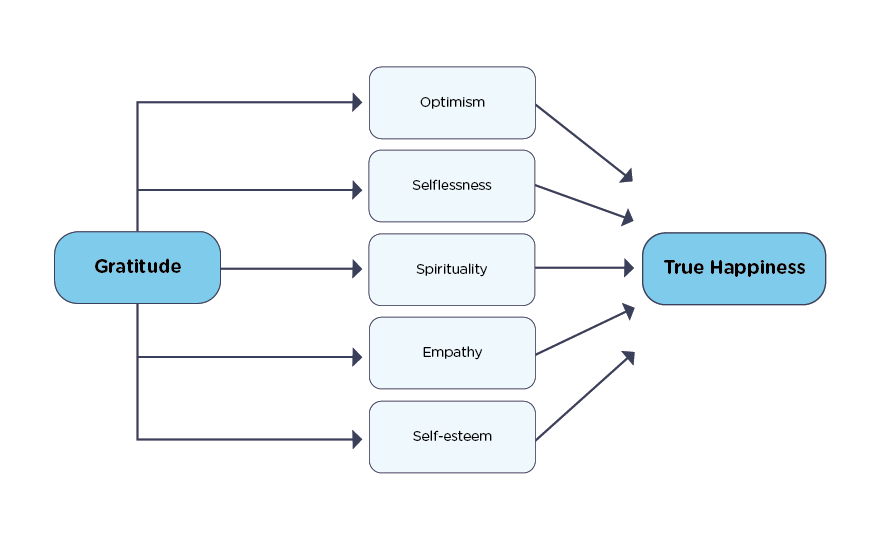

Phytic Acid as Antinutrient

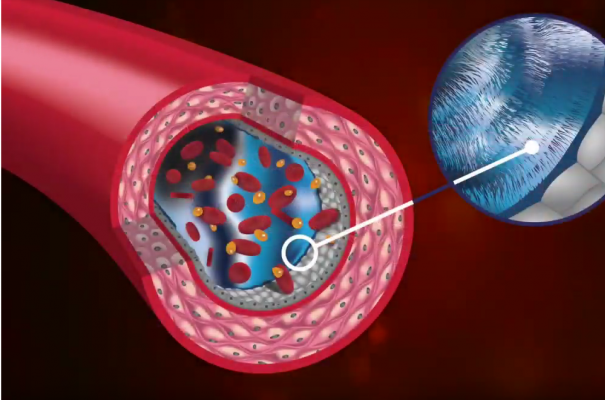

When consumed by people, phytates bind with certain nutrients and prevent their absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.

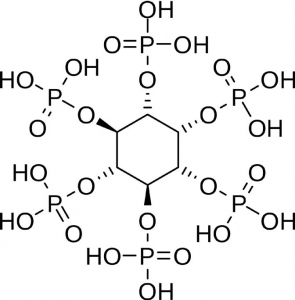

Studies show that for many people, phytic acid in whole grains blocks calcium, zinc, magnesium, iron, and copper. When the “arm” of the phytic acid molecule “chelate” or grab onto these other molecules, it becomes a phytate.

Molecular structure of phytic acid (InsP 6 ) and the establishment of complexes with dietary components. A) InsP 6 in an extremely basic environment, showing high anionic charge; B) InsP 6 bound to divalent cations such as calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese and zinc, in addition to proteins, carbohydrates and H + ions; C) InsP 6 completely protonated in an extremely acidic environment; D) sequential hydrolysis of the ester bounds that sustain phosphate groups linked to InsP 6 molecule, making phytate P and other components available for digestion and absorption. Image from researchgate.net

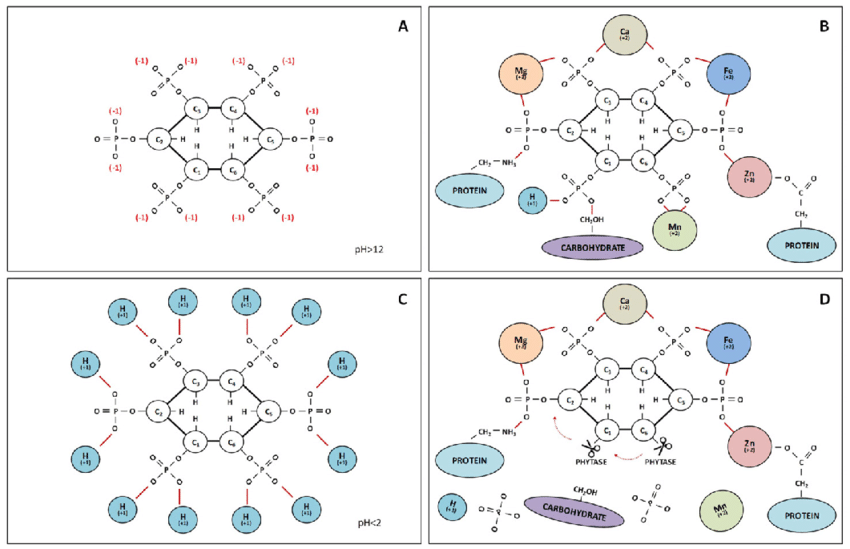

Phytates have also been shown to inhibit enzymes needed for digesting food including pepsin, amylase, and trypsin. Pepsin breaks down proteins in the stomach, amylase, breaks down starch into simple sugar, and trypsin is needed for the digestion of protein in the small intestine.

Image from researchgate.net

Phytate Immunity

Some people appear to be immune to the antinutrient effects of phytates. Researchers hypothesize this immunity may be due to the presence of beneficial gut flora that can break down phytic acid.

In addition, when consumed alongside animal fats that provide soluble vitamins A and D, the effects of phates are reduced.

Can Phytates be Beneficial?

Phytates also possess antioxidant properties. These properties have led researchers to explore their protective potential against diseases such as heart disease and cancer.

For example, researchers believe that phytic acid may be used therapeutically for the treatment of colon cancer and other cancers. But more studies need to be done to prove safety and effectiveness.

The chelating process by which phytates bond to iron and toxic minerals and removes them from the body has led to theories about their use for detoxification. Currently, phytic acid is used therapeutically to remove uranium.

However, the same ability that makes phytates able to remove uranian or iron from certain cancer cells, also depletes essential minerals from, and harms non-cancerous cells.

Foods High in Phytic Acid

All plant-based foods contain varying amounts of phytic acid that accumulates in the seeds and bran portion of plants as they ripen. Phytic acid makes up 50-85% of phosphorus in plants and is the prime source of phosphorous in legumes, oilseeds, nuts, and grains.

For humans and animals with one stomach, the tightly bound phosphorus minerals are not bioavailable.

Legumes

Legumes contain phytic acid in the inner layer of their seeds known as the endosperm. Depending on the type of legume, the phytic acid content varies from 0.22 to 2.38 grams per 100 grams.

Legumes that are high in phytic acid include:

Oilseeds

Oilseeds are seeds that can produce cooking oils. Like legumes, the phytic acid in oilseeds is stored in the endosperm. Oilseeds contain 1.0 to 5.36 grams of phytic acid per 100 grams.

Oilseeds that contain high amounts of phytic acid include:

Nuts

Most nuts have a high phytic acid content. But the amount of phytic acid can differ considerably depending on the nut. In fact, the concentration of phytic acid can vary from 0.10 to 9.42 grams per 100 grams of nuts.

High phytic acid nuts include:

Grains

Phytic acid accumulates in the husk and bran of cereal grains. Unrefined grains have the highest amount of phytic acid because they contain the entire grain — the husk, bran, and endosperm. Maize germ, wheat bran, and rice bran have up to 6.39, 7.3, and 8.7 grams of phytic acid per 100 grams, respectively.

Other cereal grains that contain high levels of phytate include:

FIGURE 1: FOOD SOURCES OF PHYTIC ACID

As a percentage of dry weight

| FOOD | MINIMUM | MAXIMUM |

| Sesame seed flour | 5.36 | 5.36 |

| Brazil nuts | 1.97 | 6.34 |

| Almonds | 1.35 | 3.22 |

| Tofu | 1.46 | 2.90 |

| Linseed | 2.15 | 2.78 |

| Oatmeal | 0.89 | 2.40 |

| Beans, pinto | 2.38 | 2.38 |

| Soy protein concentrate | 1.24 | 2.17 |

| Soybeans | 1.00 | 2.22 |

| Corn | 0.75 | 2.22 |

| Peanuts | 1.05 | 1.76 |

| Wheat flour | 0.25 | 1.37 |

| Wheat | 0.39 | 1.35 |

| Soy beverage | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| Oats | 0.42 | 1.16 |

| Wheat germ | 0.08 | 1.14 |

| Whole wheat bread | 0.43 | 1.05 |

| Brown rice | 0.84 | 0.99 |

| Polished rice | 0.14 | 0.60 |

| Chickpeas | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| Lentils | 0.44 | 0.50 |

FIGURE 2: PHYTIC ACID LEVELS

In milligrams per 100 grams of dry weight

| FOOD | mg phytic acid/100 g dry weight |

| Brazil nuts | 1719 |

| Cocoa powder | 1684-1796 |

| Brown rice | 12509 |

| Oat flakes | 1174 |

| Almond | 1138 – 1400 |

| Walnut | 982 |

| Peanut roasted | 952 |

| Peanut ungerminated | 821 |

| Lentils | 779 |

| Peanut germinated | 610 |

| Hazelnuts | 648 – 1000 |

| Wild rice flour | 634 – 752.5 |

| Yam meal | 637 |

| Refried beans | 622 |

| Corn tortillas | 448 |

| Coconut | 357 |

| Corn | 367 |

| Entire coconut meat | 270 |

| White flour | 258 |

| White flour tortillas | 123 |

| Polished rice | 11.5 – 66 |

| Strawberries | 12 |

Phytic Acid Risks: Impaired Mineral Absorption

Once ingested, phytic acid forms insoluble compounds with minerals, proteins, enzymes, and starches. This impairs the absorption of proteins and minerals such as iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium.

Deficiencies in these minerals can result in health problems including:

- Anemia

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Memory and concentration problems

- Hair loss

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Low bone mass

- Impotency in men

- Reduced immune function

Is Phytic Acid a Health Concern?

Phytic acid is not a major health concern for people eating a nutrient dense diet. But if you have higher nutritional requirements, inadequate intake, or deficiencies of minerals and trace elements, you should limit phytic acid foods.

This is especially important if you follow a vegetarian or vegan diet. Eating a plant-based diet can increase your risk of nutritional iron and zinc-deficiency.

Iron naturally occurs in plants in the form of non-heme iron. This type of iron is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract due to the presence of phytic acid.

But is also found in whole animal products like red meat and organ meat. This type of iron is known as heme-iron and is not affected by phytic acid. For this reason, individuals who eat animal-meat based diets rarely experience mineral deficiencies from phytic acid.

And though zinc occurs in decent amounts in certain grains, the phytic acid in those grains dramatically inhibits the body’s ability to absorb it.

For vegetarians, vegans, and people who live in developing countries, low intakes of meat combined with high intakes of phytic acid foods like cereal grains and legumes can lead to serious deficiencies.

Researchers estimate that 17.3% of the world’s population is at risk of inadequate zinc intake. While almost the 30% are anaemic.

How Much Phytic Acid is Too Much?

Though we recommend reducing phytates as much as possible, there is no official Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of phytic acid.

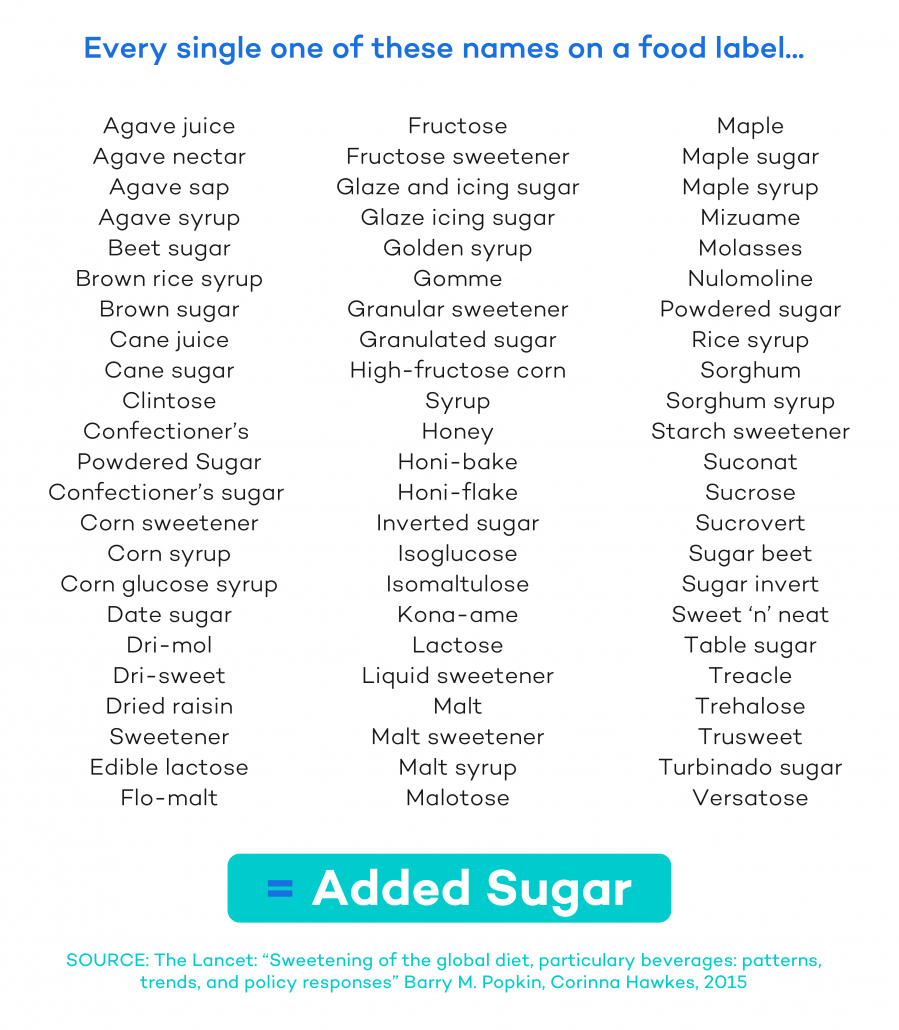

The average phytate intake in the U.S. and the U.K. is between 631 and 800 mg per day. In Finland, it’s 370 mg. It is 219 mg in Italy and only 180 mg in Sweden.

In developing countries that must rely mainly on legumes and cereal grains, and in vegetarian and vegan populations that choose to rely on these nutrient sources, intake is often as high as 2,000 mg per day.

We recommend that if you have a diet based on quality animal fats and proteins along with bioavailable vitamin D, vitamin A, vitamin C, and zinc 400-800 mg per day may be safe.

For people with bone loss, mineral deficiencies, and tooth decay, we advise less than 400 mg. For children and pregnant women, it’s best to reduce phytic acid as much as possible.

Fortunately, there are ways to prepare phytate-rich foods in ways that reduce the presence of phytates.

Dephytinization and Nutrition

Dephytinization is a sustainable way to improve the nutrition of high phytate foods. Dephytinization is the process of breaking down phytic acid to increase the bioavailability of certain minerals.

This is done using phytase, an enzyme that makes minerals available for absorption. Interestingly, phytase naturally occurs in raw plants. You can increase phytase activity through food processing techniques such as milling, soaking, fermentation, and germination.

Milling and Soaking

Milling is the process of grinding cereal grains into flour. This removes the husk and bran, the protective outer layers of grains like wheat and rice that contain high amounts of phytic acid. Milling increases protein and mineral digestibility and reduces the phytic acid content of cereal grains. However, it doesn’t always increase mineral availability.

The nutritional content of milled grains varies depending on the concentration of minerals in the husk and bran. In fact, the concentrations of sodium, calcium, potassium, magnesium, iron, barium, and phosphorous decrease in milled wheat and rice.

On the other hand, minerals such as zinc and iron increase after milling barley, rye, and oat because they are more evenly distributed throughout the grain.

While milling can increase mineral digestibility and reduce phytic acid levels, it may be most beneficial in combination with soaking.

Soaking

Submerging legumes and grains in water for a certain period of time activates the enzyme phytase. This reduces phytate levels and improves mineral bioavailability. For example, soaking pearl millet can increase the availability of iron and zinc by up to 23%.

Soaking is also a popular preparation method for nuts. However, recent research suggests that soaking nuts in water may not improve mineral bioavailability or affect phytate levels. Instead, researchers found that soaking nuts results in lower mineral concentrations.

Fermentation

Fermentation is a common food processing technique to preserve foods, improve food safety, and increase nutritional value. Fermentation leads to the production of lactic acid, which increases the activity of phytase by lowering the PH.

Phytic acid is stable at a neutral PH of 6-7. When the PH becomes acidic, phytase can break the bonds between phytic acid and minerals. This enables the absorption of minerals in the small intestine.

Lactic acid bacteria can reduce phytic acid in pseudocereals like amaranth, canihua, and quinoa.

Interestingly, fermenting cereals in flour form results in higher degradation of phytic acid than fermenting them in grain form. The fermentation of raw cereal flours increases the mineral accessibility of iron, zinc, and calcium.

The fermentation of heat-treated grains also increases the availability of minerals, but to a lesser extent. This is because heat treatment deactivates the phytase in plants. However, the phytase produced by lactic acid fermentation breaks down some of the phytic acids.

Germination

Germination occurs when a seed grows into a seedling. You can germinate beans, seeds, nuts, and grains by soaking them in water until they grow sprouts. Another common method involves soaking seeds in a wet paper towel in a disinfected, dark cabinet.

Germinating seeds reduces phytic acid by up to 40%. Incredibly, it also increases total mineral content.

Grain legumes such as beans and peanuts have significantly higher phytase activity after germinating for 6-7 days. Cereal grains such as rice, maize, millet, sorghum, and wheat demonstrate the highest phytase activity after 5-8 days of germination. High phytase activity results in reduced phytate levels and an increase in phosphorus content.

The Takeaway

Phytic acid is a compound found in plant-based foods such as legumes, oilseeds, nuts, and grains.

Since humans cannot digest phytate in the gut, and because of its high capacity to bind with other essential nutrients in diet and in the body, phytate is classified as an antinutrient.2

However, there are studies exploring the positive roles of phytic acid. These revolve around its antioxidant properties and its ability to bind with other minerals. The later function suggests that it may be used to target certain cancer cells that need iron.

But for most people, the ingestion of phytic acid is a net negative. It reduces the absorption of iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium. And in extreme cases, eating too many phytic acid foods can cause nutritional deficiencies.

The good news is that there are many ways to avoid most health problems associated with phytic acid by using different processing methods for foods high in phytic acids.

Or simply by reducing or eliminating high-phytate foods and replacing them with phytate-free, nutrient-dense animal-based foods.