We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

What is the Inuit Diet, and What Can it Teach Us?

The traditional diet of the Inuit, the indigenous people inhabiting the Arctic regions of North America, provides a unique perspective on nutrition and health. And it’s piquing the interest of a growing modern tribe of low-carb and carnivore dieters seeking a return to ancestral eating patterns.

Before the introduction of processed Western foods, the Inuit thrived for millennia, consuming an essentially carnivorous diet devoid of nearly all plant foods.

Though the traditional Inuit dietary pattern contradicts modern nutritional dogma, studies show they had robust health and remarkably low incidences of modern diseases, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and osteoporosis.

In this article, we’ll explore what the traditional Inuit diet consisted of, unearth observations of the health of traditional Inuit by early Arctic explorers, and look at the negative impact of Western foods. We’ll also consider what modern humans can learn from the Inuit’s seemingly extreme way of eating.

Table of Contents

Who Are the Inuit?

The Inuit, also called Eskimos, are indigenous hunter-gatherer peoples. They inhabit the Arctic regions of North America, including parts of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.

Despite the impacts of Western colonization and exploitation of their lands, the Inuit have retained rich cultural traditions of art, storytelling, and a deep knowledge of their ecosystems, along with the animals they have relied on for food for thousands of years.

Early dietary researchers were blown away by their robust health while consuming a carnivorous diet in such harsh conditions.

For example, in the seminal account of traditional diets, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, pioneering dentist Weston A. Price, wrote:

“In his primitive state he has provided an example of physical excellence and dental perfection such as has seldom been excelled by any race in the past or present…we are also deeply concerned to know the formula of his nutrition in order that we may learn from it the secrets that will not only aid in the unfortunate modern or so-called civilized races, but will also, if possible, provide means for assisting in their preservation.”

What did the Inuit Eat?

As hunter-gatherers in an arctic region with almost no arable land and extremely short growing seasons, the Inuit relied almost exclusively on marine and land animals. These primarily included:

- Whale

- Seal

- walrus

- Caribou

- Reindeer

- Wild birds

- Salmon and other wild fish

- Eggs from birds and fish

- Seasonal kelp

- Seasonal berries

The Inuit consumed these foods cooked, raw, frozen, and fermented.

Inland-dwelling Inuit relied more heavily on caribou that fed on the summer lichens and mosses across the tundra. Though the Inuits did not eat these plants directly, they were known to consume the pre-digested vegetation harvested from the stomachs of hunted caribou.

What we know of traditional Inuit diets comes mainly from the accounts of early explorers like the Harvard-trained anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Stefansson described the diet of the band of Mackenzie River Inuit he lived with as consisting of dried or cured meat “eaten with fat.” Much of this fat was taken from the back slab of mature caribou.

Similar observations were documented by another Arctic explorer, Hugh Brody, in his book Living Artic. Brody reported that the Inuit prized raw liver mixed with small pieces of fat. And they also spread fat or lard on dried and smoked meat.

No Essential Foods, Only Essential Nutrients

To our Western minds steeped in “balanced diet” dogma calling for a plethora of whole grains, legumes, veggies, and fruits with limits on dairy, eggs, meat, and fat, the Inuit diet may seem extremely imbalanced.

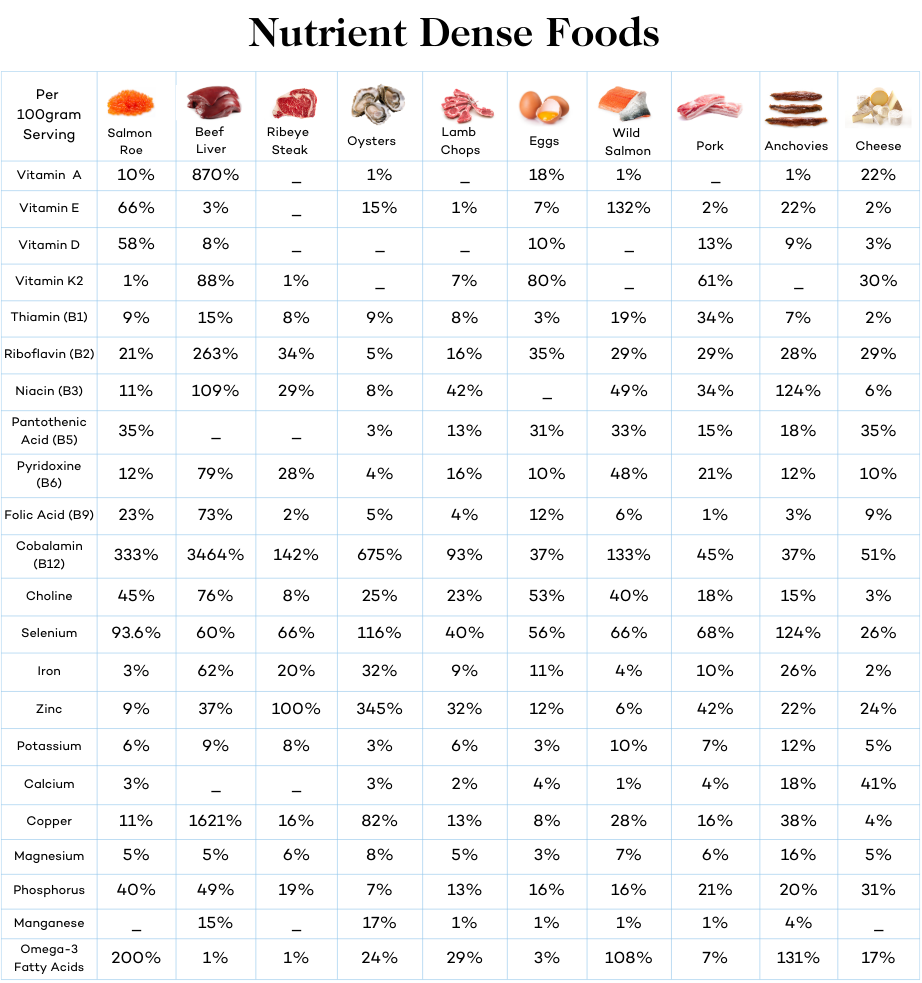

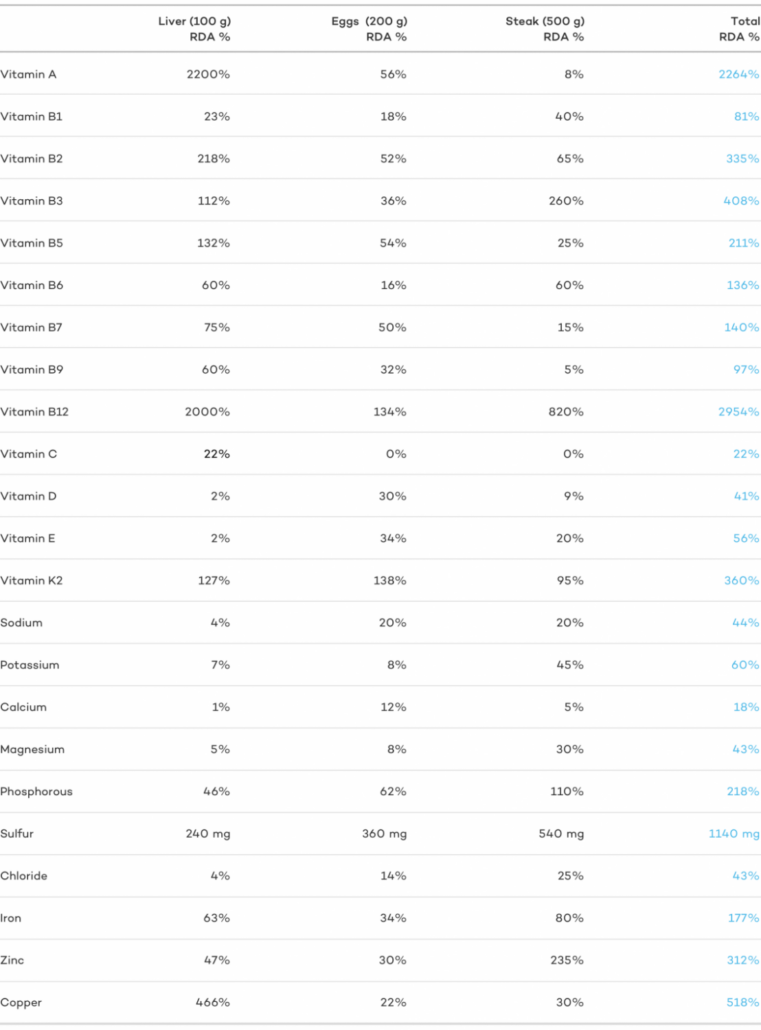

Yet what’s missing in this dogma is an honest acknowledgment that animal products are far and away the most nutrient-dense foods on earth.

In other words, animal products have more macro and micronutrients per weight than plants with regard to variety, total amount, and absorbability.

Plants are completely non-essential, while meats are optimal. Meat is much more than fat and protein.

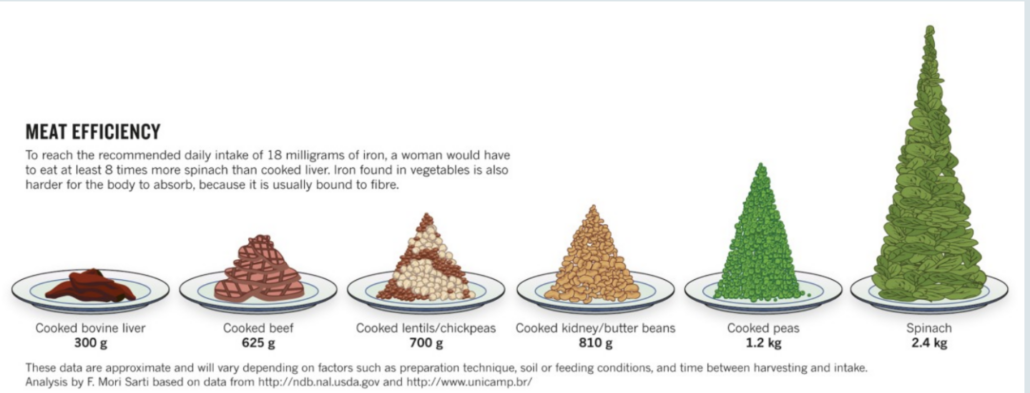

Take Iron, for example. The iron found in animal products is called heme iron. This type of iron is far more absorbable than the non-heme iron found in plant foods.

Furthermore, to get the same amount of iron as 300 grams of liver from spinach, you’d have to eat 5.2 pounds, and it would still be of an inferior type. This phenomenon is known as “meat efficiency.” But we might as well call it what it is: meat superiority.

Source: Gupta, S. Brain food: Clever eating. Nature 531, S12–S13 (2016)

Though the Inuit hunter-gatherer diet is shaped by the extreme northern climate and limited growing season, it is very close to the hypercarnivorous eating pattern that our ancestors practiced for nearly two million years before the advent of agriculture only 10,000 years ago–a mere blip on our dietary timeline.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the key foods and nutrients in the traditional Inuit diet.

High-Quality Animal Fats

Most modern people think of meat as red muscle meat. But for the Inuit, meat meant lots of glistening white fat.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson observed Inuit hunters targeting older and, therefore, larger male animals, specifically because of their enormous slabs of back fat that weighed 40-50 pounds and the highly saturated fat surrounding their kidneys. While coastal groups prized the blubber from whales, seals, and walrus.

These wild animal fats are high in beneficial omega-3 fatty aids, along with monounsaturated and saturated fats.

For example, whale blubber is about 70 percent monounsaturated fatty acids and nearly 30% omega-3s.

Monounsaturated fatty acids have been found to

- Improve blood lipid levels

- Help you shed excess weight

- Protect against inflammation

- regulate insulin sensitivity

- support cognitive function

If you’re surprised to see the word “healthy” alongside “saturated fat,” you’re not alone. Since the 1960’s saturated fat has been demonized as the root of heart disease, yet modern research tells us that this is not the case.

Saturated fats support numerous physiological functions, including

- Cellular Structure: Saturated fats make up around 50% of the membranes of cells, maintaining their structural integrity and function.

- Nutrient Absorption: Saturated fats are critical to the body’s ability to absorb fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). These vitamins are essential for survival and play key roles in nearly every physiological function, including childhood development, immune function, bone formation, vision, and heart health.

- Hormone Production: Important hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, require saturated fats for their production.

- Brain Health: The brain consists of 60% fat, much of it saturated. Very long chain saturated fatty acids that the Inuit get from fish and seafood support the structural integrity of brain cells and support cognitive function.

Fat Soluble Vitamins

The animal products that the Inuit relied on are remarkably rich in fat-soluble vitamins.

Weston A. Price identified these fat-soluble vitamins as the key to robust health and the absence of disease among the traditional peoples he studied, including the Inuit.

His analysis of traditional diets revealed that they provided at least 400% of minerals, including calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and 1000% more vitamins A, D, E, and K2 than a Western diet.

These findings accord with the Inuit diet that enters around the richest sources of fat-soluble Vitamin A (as retinol), vitamin D, and K2 :

- animal fats

- organ meats, especially ruminant liver

- fatty fish

- fish eggs (roe)

- Shellfish

- Eggs (for Inuit, from wild birds)

Without the fats and fat-soluble nutrients found in these animal products, most essential nutrients, including protein, water-soluble vitamins, and minerals, are not fully absorbed and used by the body.

What About Vitamin C?

The prevailing dietary misconception is that you need to get vitamin C from plant foods or you’ll get scurvy–a collection of symptoms including bleeding gums, inability to heal wounds, joint pain, and general physical and mental degeneration.

However, this is only the case in the context of a Western diet based on grains, sugars, and processed meats.

In fact, protection from scurvy comes from just 10 milligrams of vitamin C per day. This intake is easily achievable from even fresh conventional beef. While traditional Inuit foods provided substantially more.

The vitamin C content of traditional Inuit diet foods includes:

- muktuk–whale skin and blubber–(36 milligrams per 100 grams). Per weight, this is as much vitamin C as orange juice

- Raw caribou liver (24 milligrams per 100 grams)

- Seal brain (15 milligrams per 100 grams)

- kelp (28 milligrams per 100 grams)

Modern (2007) research on the vitamin C in meat reveals that fresh beef provides approximately.

- 1.6 mcg/g of vitamin C in grain-fed meat

- 2.56 mcg/g in grass-fed meat

| Beef Muscle Meet (1000 grams/2.2 lbs) | Amount Vitamin C | % sufficient to prevent scurvy |

|---|---|---|

| Grass-fed beef | 2.56 mg | 25% |

| Grain-fed beef | 1.6 mg | 16% |

Vitamin C in Organ Meats and Seafood

Various seafood and organ meats provide more than enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy. [19][20][21].

| Animal-Based Foods High in Vitamin C | Amount Vitamin C | % sufficient to prevent scurvy |

| Beef spleen (100g) | 45.5mg | 455% |

| Beef thymus (100g) | 34mg | 340% |

| Salmon Roe (100g) | 16 mg | 160% |

| Beef Pancreas (100g) | 13.7 mg | 137% |

| Chicken giblets (100g) | 13.1mg | 131% |

| Beef Brain (100g) | 10.7 mg | 107% |

| Beef Kidney (100g) | 9.4 mg | 94% |

| Oysters (6 oysters, or 88 grams) | 3.3 mg | 33% |

| Raw Liver (100g) | 1.3 mg | 13% |

Protein Constraint

In his studies of North American Native people, Stefansson identified a phenomenon he called “meat hunger” among tribes that depended on lean meats during periods without access to fatty animals like moose, bear, fish, or large sea mammals.

Eating only lean meat resulted in “diarrhoea in about a week, with headache, lassitude, a vague discomfort. If there are enough rabbits, the people eat till their stomachs are distended; but no matter how much they eat they feel unsatisfied. Some think a man will die sooner if he eats continually of fat-free meat than if he eats nothing.” Stefansson points out that deaths from “meat hunger” were rare because the native peoples were familiar with it and knew that they needed to eat more fat.

In modern terms, what Stefannson witnessed was the natural human protein constraint. When humans cut carbs and don’t get the majority of calories from fat, the liver converts protein into glucose for energy. This process creates nitrogen waste that is converted into urea. The kidneys are then tasked with eliminating the urea.

When consuming low carbs and high fat, the body becomes efficient at turning fat into potent energy molecules called ketones. This reduces glucogenesis to low, sustainable levels.

But too little fat and too much protein lead to protein poisoning. Symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, and in extreme cases, death.6

Stefansson and a friend experienced the protein constraint when demonstrating the benefits of the carnivorous Inuit diet to Western skeptics by consuming only meat for a year under the observation of physicians at New York’s Bellvue hospital.

Stefansson and his friend thrived for months on the diet until they were encouraged, for the sake of experimental observation, to eat only lean meat.

Reducing fat quickly resulted in“diarrhea and a feeling of general baffling discomfort.”

But these symptoms were rapidly reversed after consuming a single feast of fatty brains fried in bacon fat.

After this episode, the observers determined that the ideal ratio on a zero-carb diet was 75% calories from fat and 25% from protein.

What Happens When Inuit Eat Western Foods?

Various studies show that when Western diets are introduced to Inuit societies, health markers plummet.

A 2012 study comparing two physically active Inuit groups consuming either a Western or a traditional Inuit diet found that the Western diet group had higher levels of small dense LDL-C particles and higher total cholesterol and HDL-C concentration. Both of which are heart disease risk factors. 5

Other studies show that the modern Inuit have high rates of diabetes and obesity. Their deterioration in health is attributed to the consumption of white flour, sugar, and processed oils.

What Can We Learn From the Inuit Diet?

The ancestral diet and lifestyle of the Inuit resemble the hypercarnivorous diets that humans evolved on for nearly 2 million years before the advent of agriculture.

The robust health of Inuit consuming a traditional diet is a testament to the ability of humans to thrive on a high-fat, low-carb, mostly carnivorous diet. Plant food and carbohydrates are non-essential.

In fact, there are no essential foods; rather, there are optimal, nutrient-dense foods that provide essential nutrients. Animal products, including meat, seafood, and eggs, are the most nutrient-dense foods and, therefore, the most optimal.

Shifting ancestral eating patterns to processed Western foods is the root cause of diseases of civilization.