We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

Is Lab-Grown Meat Bad? A Look at the Impacts and Natural Alternatives

Lab-grown, or “cultured” meat is emerging as a new trend in the realm of food technology. This quickly growing sect of food science eliminates the need to raise as many farm animals for food and claims to be more sustainable for the environment. But is this truth or marketing? Simply put, is lab-grown meat bad or good for our environment and our bodies?

Food security and climate change are two of the biggest issues we face as a human race. So, what does this new food technology mean for the human diet and our physiological health and environmental habitats?

In this article, we’ll examine the history and science behind lab-grown meat and how it compares to both conventional and regeneratively farmed meats, both from a human health perspective and from a global point of view.

Table of Contents

What is Lab-Grown Meat?

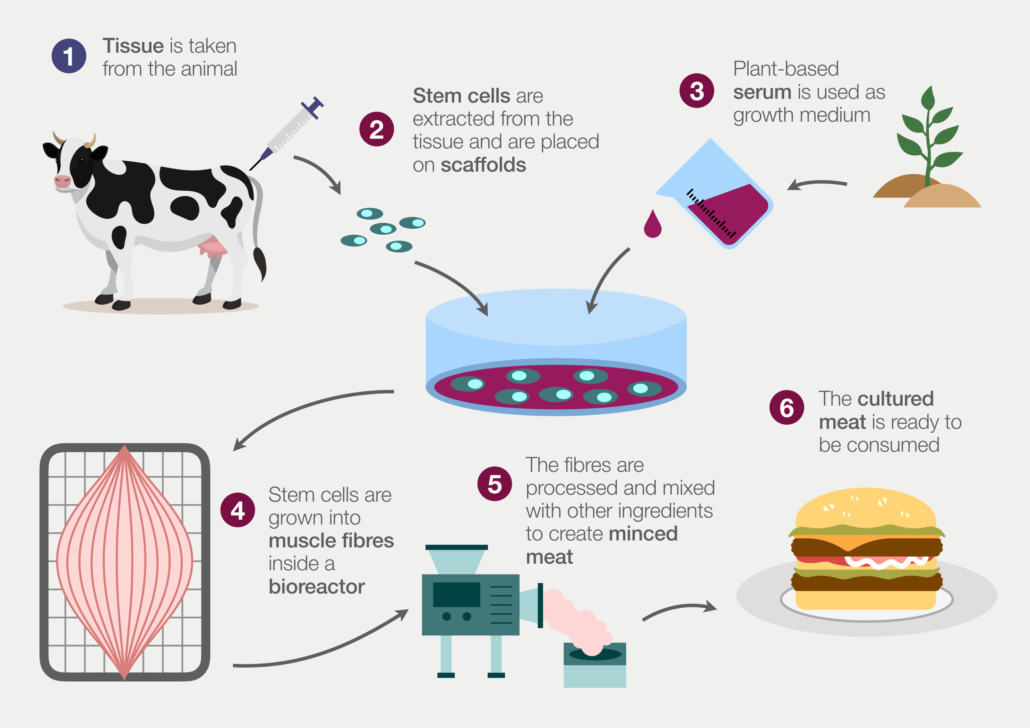

Lab-grown meat, also known as “cultivated” and “cultured” meat, is a type of cellular agriculture produced by growing animal cells in a laboratory setting using the process of in vitro.

In vitro is Latin for “within the glass.” It simply means experimenting with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context.

In 2013, the first cultured beef patty was created at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Less than a decade later, in 2020, the world’s first commercial sale of cell-cultured meat occurred at a restaurant called 1880 in Singapore.

The US is the second country to allow the sales of lab-grown meat, led by two California-based companies given the green light by the USDA in 2023.

This may seem like a relatively quick turnaround from lab to table, but this technology is built on decades of research in stem cell biology, tissue engineering, fermentation, and chemical engineering.

The process of lab-grown meat begins with collecting stem cells from animals. These cells are then grown in bioreactors, or cultivators, and fed an “oxygen-rich cell culture” that includes amino acids, glucose, and vitamins as well as supplemental growth factors, hormones, and other proteins.

Source: Shutterstock

In the European Union, the use of hormone growth promoters in conventional meat production is prohibited, which calls into question the viability of this technology.

In essence, cultured meat is a highly processed product that uses biopharmaceutical techniques to grow animal muscle and fat. Food scientists have taken away the elements that feed and nurture most animals, including human beings– sunlight, soil, water, and grasses.

Impact of Lab-Grown Meat & the Environment

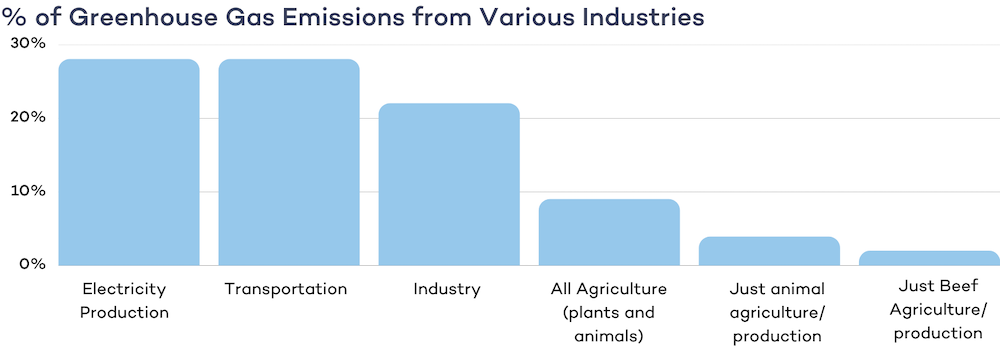

The arguments for lab-grown meat usually insist that it is better for the environment because it requires less land and water while producing less greenhouse gas emissions. However, this myth is quickly busted when taking a closer look at the production methods of cultivated meat.

While it’s too early to quantify, the long-term emissions from cultivated meat are still significant. The reasons for this include:

- bioreactors used to house and maintain animal cells

- energy needed to purify growth media, requiring similar biotechnology to pharmaceutical production

In a controversial study, a team of scientists at UC Davis set out to quantify the estimated climate impact of cultured meat versus animal agriculture in an analysis known as life-cycle assessment. This assessment covered energy use, water, and materials needed for production. They divided their outcomes into two theoretical scenarios.

One scenario assumed that the mode of production of cultivated meat would resemble the biopharmaceutical industry, specifically as it pertains to the intense purification processes in the removal of contaminants and the energy and materials needed to maintain these levels of purity. The researchers estimated that the climate impact of highly purified meat cultivation would result in carbon dioxide emissions between 250 to 1,000 kilograms.

The other scenario assumed that cultivated meat production would instead rely on typical food-grade standards and not require ultra-high-purity ingredients. This food-grade scenario would result in the equivalent of 10 to 75 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions.

Compare these emissions to standard feedlot beef at 15 kg of emissions per kilogram of beef.

Beef raised with regenerative agricultural practices can actually sequester carbon–literally getting it out of the air and into the earth where it grows the grass that feeds cows that feed us. More on this below.

It’s also worth putting the emissions of beef production in perspective: Beef production in America accounts for only 2% of greenhouse gas emissions. That’s a small fraction considering the unrivaled nutrient density it provides millions of people.

The reality of greenhouse gas emissions and meat production :

- 28% of greenhouse gas emissions are from the production of electricity

- 28% of are from transportation

- 22% are from industry

- 9% are from all agriculture, including plant and animal production

- 3.9% of total us greenhouse gas emissions come from animal agriculture

- 2% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from beef production

Can we do a better job of producing beef in a cleaner way? Certainly. Many smaller farms are taking the lead. But the reality is that even if nothing changed in how we produce beef, lab-grown meat is very likely not an improvement for the environment and potentially much worse.

Lab-Grown Meat and Human Health

Another key issue with lab-grown meat that scientists are raising questions about is its potential impact on human health.

Cultured meat goes through a process of high-level cell multiplication. As in cancer cells, some dysregulation is likely to occur in this process. The effects of these irregularities on human health and metabolism are not known. Yet we have a lot of research on the effects of fresh red meat on human health–in short, it’s remarkably healthy. Don’t take our word for it; follow the science here.

Another factor in question is the nutrient composition of cultured meat. It is still unclear whether lab-grown meat can supply the same levels of micronutrients and iron to the body. Moreover, the use of antibiotics is a big question for the industry as it can lead to antibiotic resistance in humans.

We are seeing a science in its very early stages. Yet, as you read this article there are currently billions of dollars being invested in cultivated meat labs. The question will be how they will choose to industrialize the process and shift to large-scale production.

Additionally, food scientists have not been able to replicate the composition of real muscle which is made up of organized fibers, blood vessels, nerves, and connective tissues. They are still a far cry from a cowboy cut ribeye.

It’s also important to highlight that meat, as far as human dietary needs are concerned, actually means fat and muscle.

Our primary micronutrient requirement is fat. Protein is important but supplemental. Our national shift away from animal fats and towards industrial seed oils has been a nutritional disaster, driving rates of all-cause mortality, inflammation, cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Making the Case for Grass-Fed Meat

One of the arguments for lab-grown meat is that it could be more sustainable in feeding the growing global population.

While feedlot farming focuses on a grain-fed diet and keeping animals in an enclosed area for most of their lives, grass-fed farming is based on regenerative farming practices like restoring soil microbial diversity, no-till planting, and adaptive multi-paddock grazing.

Grassland farming systems promote biodiversity and make the land more resilient to flooding and drought. Returning cattle and other ruminant animals to the land for their entire lives can also boost the nutrient content and flavor of livestock and plants. At the same time, the increased grasses can trap more atmospheric carbon dioxide.

One study found that a 3,200-acre farm in Georgia stored enough carbon in its grasses to offset not only the entire methane emissions produced by its grass-fed cattle but also most of its total farm emissions.

New research is emerging on the nutritional benefits of grass-fed farming over feedlots, including higher essential fatty acids such as omega-3.

If the private and public institutions with the greatest influence on our food systems are serious about reducing carbon while producing nutrient-dense foods, then investing in regenerative agriculture appears far more deserving of those billions of dollars than pharmaceutical “food” factories.

If growing meat is such a complex issue then why don’t we all just go plant-based? Because humans evolved as fatty-meat-eating machines. Our bodies and brains depend on meat for optimal health and well-being. We’re not designed to eat loads of plants.

It’s also worth noting this eyebrow-raising 2016 study from Carnegie Mellon University, revealing that if Americans followed the mainstream dietary recommendations for a ‘healthy’ mix of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and seafood.

- energy use would go up by 38%

- water use by 10%

- greenhouse gas emissions by 6%

That 2% of greenhouse gasses is doing a lot of nutritional lifting on a population level. Eating more beef and less of these other recommended foods is actually protecting against increased greenhouse gas emissions.

The Importance of Meat in the Human Human Diet

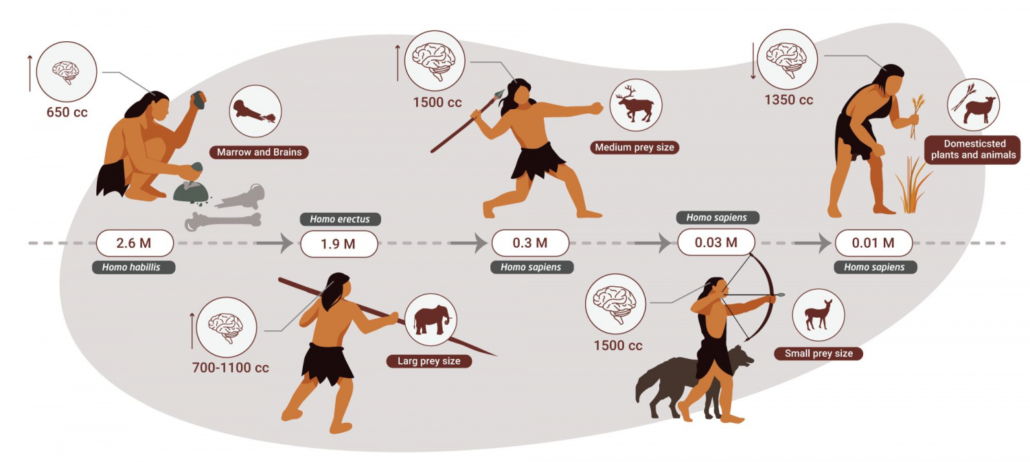

Humans and our pre-human ancestors have been consuming meat for 2 million years. In fact, for nearly 2 million years until only around 10,000 years ago, humans were considered “hyper-carnivorous” apex predators that ate a diet primarily of the meat of large land animals.

Source: Dr Miki Ben Dor

Our divergence of the hominin line from other apes in Africa is in large part due to a gradual climate change, which dried the grasslands and made plants less readily available, thereby leading to a dietary shift towards fat and protein.

This ancestral dietary shift impacted major physiological and metabolic adaptations in early humans that resulted in larger brains in proportion to their body size and a reduced gut and G.I. tract.

In a 2023 study in Animal Frontiers, researchers noted, “This process required a shift from a diet high in bulky plants of low digestibility (requiring voluminous fermentation chambers such as a rumen or cecum, or an extensive colon), to a higher-quality diet where foods are more energy dense and require less digestive processing. In temperate grass and woodland environments, this equates to an animal-derived protein-rich and fat-rich diet.”

Our substantial intake of meat as early humans is the foundation of our extraordinary human brain, our unique digestive tract among primates, and our fat-based metabolic abilities.

The deviation of the standard American diet away from our ancestral diet of animal-based whole foods is a major factor in chronic inflammatory illnesses today.

In contrast, a meat-based high-fat, nutrient-dense approach eliminates the grains, sugars, and seed oils that drive inflammation. Doing so reduces this risk of autoimmune disease and type 2 diabetes while improving cognitive function, mood disorders, and fertility.

The Bottom Line: Why Lab Grown-Meat is Bad

As humans, we continue to push the limits of discovery, and lab-grown meat is marketed as a way to spare animal lives while protecting the environment. However, when examining the energy-intensive processes involved in lab-grown meat and the complexity of creating animal muscle (let alone the fat we really need), these fantasies appear to be extremely expensive, nutritionally limited, and ultimately unlikely.

Considering that modern regenerative meat farmers have demonstrated that meat production can be humane, nutritious, and carbon-sequestering, it makes far more sense to turn our attention and our dollars toward supporting and scaling these practices.

Grass-fed and regeneratively farmed meat has the capacity to restore ecosystem balance and make our environments more resilient to natural disasters. Not to mention the increased health and nutritional value of its output versus lab-produced muscle.