We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

Glycoalkaloid: AKA Potato Poison

Glycoalkaloid is one of the many plant defense mechanisms that plants have evolved to protect themselves from being eaten by animal predators and from infection by bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Consider that plants don’t have fangs, fists, claws, or feet. But what they lack in these areas they make up for with an arsenal of chemical defenses known as phytoalexins.

Glycoalkaloids are nitrogen-containing plant toxins found naturally in species of the Solanaceae family, including [1]:

- Potatoes

- Tomatoes

- Eggplants

- Peppers

Different plants have different concentrations and types of glycoalkaloid. For instance, the glycoalkaloids in potatoes often referred to as ‘potato poison’ are alpha-chaconine and alpha-solanine. These are more toxic than those found in tomatoes called alpha-tomatine and dehydrotomatine.

For such a common and potentially harmful plant toxin, glycoalkaloids are news to most people. This article is here to change that. Let’s explore what glycoalkaloids are, how they affect humans, and how to protect yourself.

Table of Contents

How Glycoalkaloids in Food Affect Humans

When ingested by humans, these toxins can act as neurotoxins and enzyme inhibitors with sometimes fatal effects [1].

Research suggests that the common potato glycoalkaloids alpha-solanine and alpha-chaconine are absorbed into the bloodstream, take a long time to break down, and can therefore accumulate in humans [2].

At high enough concentrations, glycoalkaloids can do damage by weakening the membranes of red blood cells, entering the cells, and destroying the cell mitochondria–the parts of cells that generate energy.

Research suggests that the cell-rupturing effect may cause intestinal permeability known as “leaky gut” [3][4].

Leaky gut allows pathogens and sugars from the intestines to cross into the bloodstream, where they are transported throughout the body. This can result in glycation–the harmful bonding of sugar molecules to tissues and organs–chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

Learn how to reduce leaky gut through diet here.

In animal studies, glycoalkaloids have been shown to negatively interact with a thin cellular membrane called the glycocalyx in the intestine resulting in limited nutrient absorption [5].

Other animal tests have shown that glycoalkaloids can cause birth defects [6]. But as is the case with many plant toxins and antinutrients, glycoalkaloid needs to be studied in greater depth to understand their full effects on humans.

Symptoms of Glycoalkaloid Poisoning in Humans

Glycoalkaloids are abundant in white potatoes and can cause signs of toxicity when consuming just 1 kg of potatoes.

Having a healthy GI tract reduces the likelihood of reactions to glycoalkaloids. But even for healthy people, consuming large amounts of potatoes, especially when green, damaged, or sprouting, glycoalkaloids can accumulate and lead to toxicity.

In humans, symptoms of mild to moderate glycoalkaloid poisoning include [7]:

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Apathy

- Restlessness

- Drowsiness

Low-dose glycoalkaloid toxicity can result in vomiting and diarrhea. While exposure to high doses can cause serious symptoms, including [8][9]:

- Fever

- Low blood pressure

- Weakness

- tremors

- Spina bifida birth defect

- Fatality

Cognitive symptoms of acute glycoalkaloid toxicity include:

- mental confusion

- Rambling

- Incoherence

- Stupor

- Hallucinations

- Dizziness

- visual disturbances

Humans can experience glycoalkaloid toxicity when ingesting as little as 1 mg of glycoalkaloids per kg body weight.

3 mg/kg of body weight can lead to death. To put this into perspective, a 150 lbs person can experience toxicity when consuming 68 mg of glycoalkaloid, while consuming 302 mg may be fatal.

Health Canada has established a maximum level of 20 mg of total glycoalkaloids per 100 g (fresh weight) of potatoes consumed [10].

Glycoalkaloid levels in common potato products [11]

| FOOD TYPE | CHACONINE | SOLANINE | TOTAL GLYCOALKALOID CONCENTRATIONS |

| POTATO CHIPS (1 OZ BAG) | .36-.88 mg | .29-1.4 mg | 2.7 -12.4 mg/ 28 gram bag |

| FRIED POTATO SKINS (4 OZ) | 4.4-13.6 mg | 2.0-9.5 mg | 6.4- 23.1 mg/4 oz |

Are there Benefits of Glycoalkaloids?

As with other plant toxins, there have been preliminary studies looking at the potential uses of glycoalkaloids to treat cancers.

However, this is not a compelling reason to consume them. The ability of glycoalkaloids to destroy cells–called “apoptosis”–can damage and destroy both cancer cells and healthy cells. One way to think about it is like chemotherapy. Though it may kill cancer cells, there are side effects.

Furthermore, these studies have only been conducted in vitro and have yet to be attempted with live animals or people [12].

Potato Poison

If you’ve ever heard people talking about ‘potato poison’ they’re talking about glycoalkaloids. White potatoes have the highest glycoalkaloid levels of foods that we normally eat.

In potatoes, the poison is concentrated in the sprouts, peel, and area around the “eyes.”

Potatoes can accumulate greater levels of glycoalkaloid when stored in ways that expose them to lots of light i.e. on a shelf. This results in a “greening” effect which occurs when chlorophyll forms in the potato skin. Chlorophyll forms in conjunction with glycoalkaloids, so noticing a greening effect is a sign of potato poison and a reason to discard them.

Damage to potatoes also causes accumulations of these toxins. They show up at the sites of damage to protect the vulnerable area from infection by bacteria, pests, and viruses.

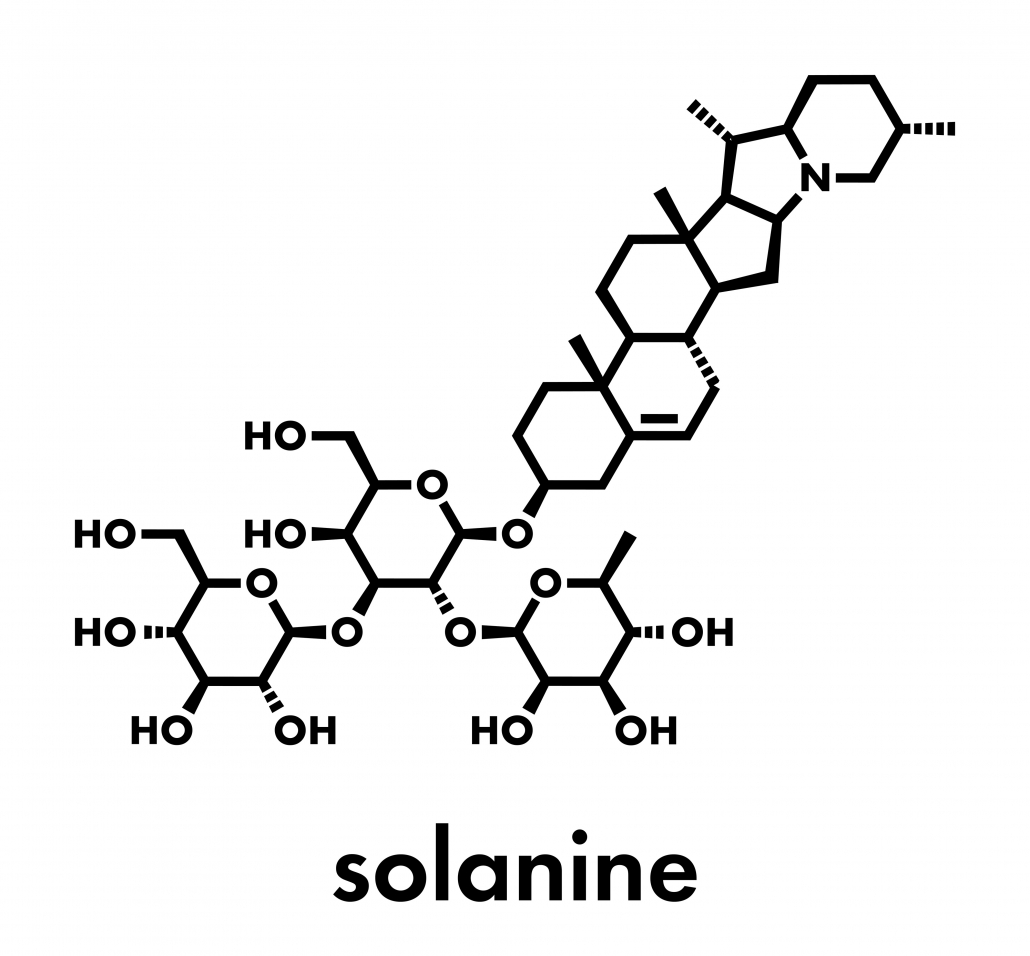

Alpha Solanine

Alpha-solanine is the most infamous of glycoalkaloids. It’s found in nightshades, including eggplants, tomatoes, peppers, potatoes (white, not sweet), and paprika.

Solanine is also found in lower concentrations in some non-nightshades, including apples, cherries, okra, and beets.

Solanine is the compound that destroys red blood cells and is responsible for symptoms of inflammation and intestinal irritation.

Studies on rats show that consuming solanine from potatoes exposed to light results in tissue damage and worsen symptoms of arthritis [13]

In humans, solanine consumption can exacerbate irritable bowel syndrome, heartburn, acid reflux, and other GI issues.

Solanine and its tomato counterpart ‘tomatine’ can accumulate in the body and become mobilized in times of stress.

For this reason, many health professionals recommend eliminating potatoes, tomatoes, and other nightshades, particularly for people who have arthritis, digestive disorders, and autoimmune disorders [14].

How to Avoid Glycoalkaloid

Beware that cooking does not significantly reduce glycoalkaloids.

This means it’s important to store potatoes in low light, hence the age-old practice of root cellars.

Discard any potatoes and other nightshades showing. signs of damage, sprouts, or green areas.

Peel your potatoes since this is where most of the toxins accumulate. And do not eat bitter-tasting potatoes.

Glycoalkaloid: The Bottomline

Glycoalkaloid is a family of toxins that naturally occur in plants as part of their chemical defense system. They occur in abundance in plants within the Solanaceae family, including potatoes, tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers.

These toxins fend off pests, bacteria, and viruses. But these same properties that protect plants can be toxic to humans, destroying cells and interfering with neurotransmitters. Symptoms range from fatigue to autoimmune disorders and even death.

To reduce exposure to glycoalkaloid, we advise reducing the intake of plants within the Solanaceae family. When consuming potatoes, make sure they are not green, sprouting, damaged, or bitter tasting. It is also best practice to peel potatoes since these toxins accumulate in the skins.