We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

The Keto Diet and Human Evolution

The keto diet has been around for as long as humans have walked the earth. This is because keto is not really a diet; it’s a metabolic state critical to human evolution.

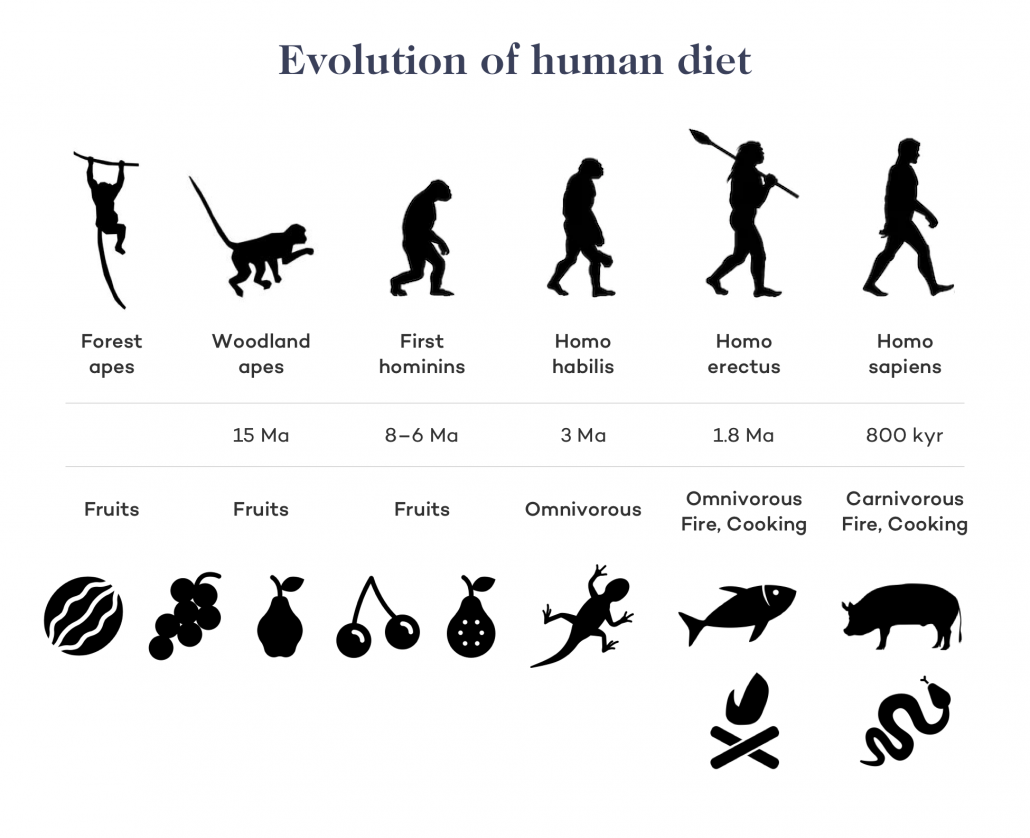

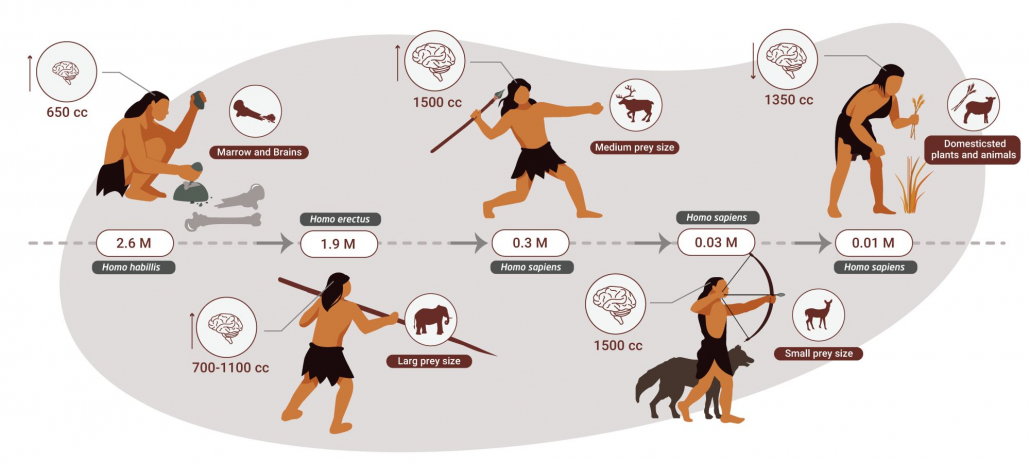

Humans evolved the ability to eat keto as we left behind the vegetarian diet of our primate ancestors and began scavenging and hunting meat.

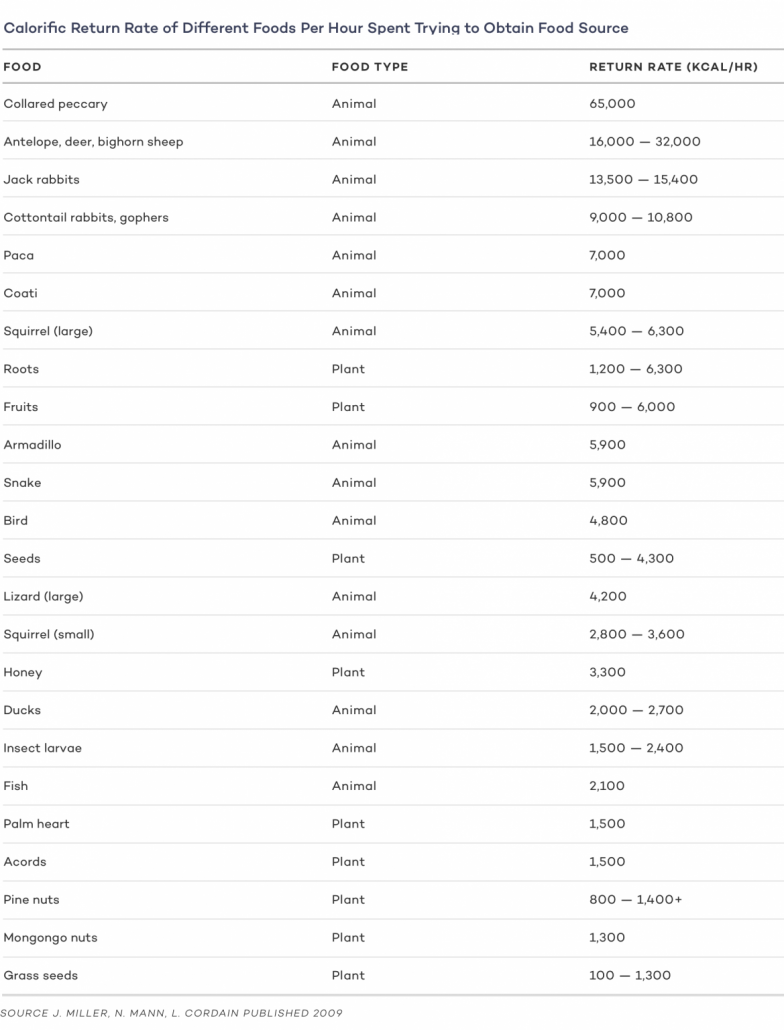

For the vast majority of human history—we’re talking hundreds of thousands of years—humans lived as hunter gatherers. Our diets consisted mostly of wild meats and, to a lesser degree, low nutrient plants.

By ‘meats,’ we mean the whole animal–especially the mineral-rich fat, marrow, and organs.

Table of Contents

Our Eating Habits are Not What They Used to Be

Our eating habits are not what they used to be–10,000-200,000 years ago. On one hand, we eat way more processed, calorie-dense junk food. On the other, we listen to an army of professional nutritionists admonishing us to replace junk food with a so-called “balanced diet” of grains, fruits, and vegetables.

We came out of the trees not to eat the grass, but to eat the grass eaters!

What most nutritionists miss is the fact that 72% of what we consume today did not exist in the diets of our ancestors. This covers both processed foods and our various “natural” foods. The diet humans evolved to eat looks radically different from what we’re “supposed” to eat today.

Raymond Dart, the man who discovered the fossil of our first human ancestor in Africa, describes the earliest humans like this: “carnivorous creatures, that seized living quarries by violence, battered them to death … slaking their ravenous thirst with the hot blood of victims and greedily devouring livid writhing flesh.”

Though Dart’s description might ring a bit over-the-top, it captures the truth of our dietary origins: We came out of the trees not to eat the grass, but to eat the grass eaters!

Our caveman ancestors ate as other large meat-eating mammals do.

For example, our fellow kings of the jungle—lions and tigers—first devour the blood, and fatty organs including hearts, kidneys, livers, and brains, leaving much of the lean muscle to the vultures. Fat, as we will see, is, and has always been, the cornerstone of human dietary health.

The Keto Diet and Evolution of the Human Brain

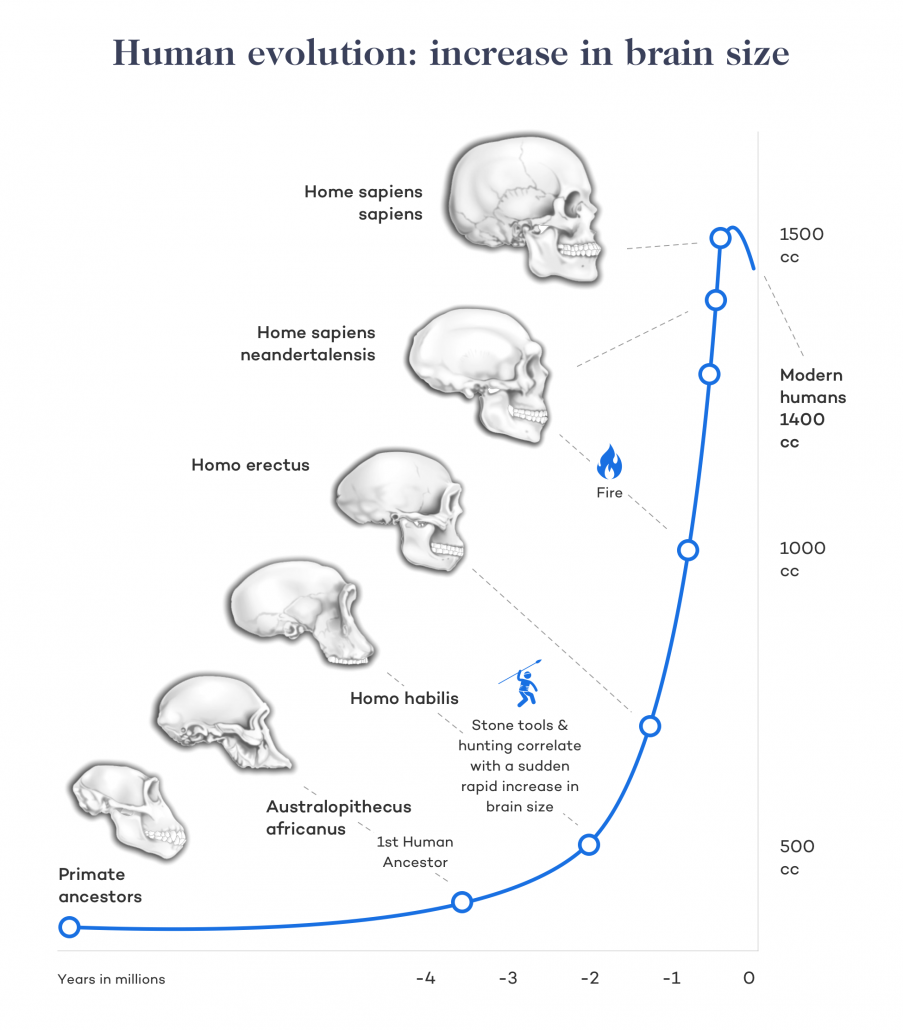

A consensus of scientists believes that a diet centered on animal fat was crucial to the evolution of humans’ large brains.

So the story goes, about two million years ago we evolved the hunting techniques mentioned above. Hunting allowed us to capture and eat nutrient-dense animal foods loaded with calories, healthy keto fats, protein, organs meats, and marrow instead of the low-nutrient plant diet of apes.

Homo Erectus could then take in a surplus of energy at each meal compared with our direct primate ancestors. This higher quality fuel allowed us to eat less plant fiber which is bulkier than meat, leading us to evolve smaller guts.

With less energy going to our gut for digestion, more energy was free to fuel our brains.

The results of this evolutionary split are apparent in the fact that the human brain requires a whopping 20 percent of our energy when resting. While an ape’s brain requires only 8 percent.

The key takeaway is that the human body and brain has evolved to depend and run optimally on a diet of energy-dense food. There’s nothing that packs more energy than fatty meat.

Humans were Scavengers Before Hunters

Challenging the theory that hunting first led to humans consuming animal flesh, a recent study by Anthropologist Jessica Thompson proposes a new theory about the transition to large animal consumption by our ancestors.

The prevailing story, supported by fossil evidence from sites in Africa, is that the emergence of flaked tools for hunting and scraping meat led to the brain growth that rocketed human evolution more than 2 million years ago.

Based on the evidence of ancient animal bones, Thompson and her colleagues have a different take: Earlier hominins (pre-humans) first bashed bones to harvest fatty nutrients from bone marrow and brains. Sharpened stones for hunting and scraping meat from animals came much later.

From this perspective, scavenging and consuming fat allowed proto-humans to evolve the brains that eventually made humans smart enough to take down much larger, faster, and stronger prey.

Ancient humans ate mostly meat and specialized in hunting large animals, according to new research. (Miki Ben Dor)

How Ketosis Evolved in Humans

Ketosis evolved in the early humans we descend from. They thrived on a narrow variety of foods. And only ate when their hunting and foraging was successful. When food wasn’t available, they fasted or ate very little until they found new food sources.

Going without food and reduced carbohydrates, especially during winter months in northern regions, caused the body to release fatty acids from fat stores. These fatty acids were converted into ketone bodies, which like glucose, can be used to make ATP, the energy currency for the body.

Compared with the Standard Western Diet of today, hunter-gatherer diets from the late Paleolithic Era likely exhibited the following nutritional characteristics:

- Significantly higher fat

- Higher protein

- Much lower carbohydrates

- Lower glycemic load

- More vitamins, minerals, especially A, and D

- Higher potassium and lower sodium levels

Fascinatingly, fatty acids are more efficient than glucose for producing energy, especially in tissues with high-energy requirements like the heart where 50-70% of energy comes from fatty acids.

Over hundreds of thousands of years as hunter gatherers, humans evolved bodies that are optimized to run without carbohydrates, to go periods without eating, to thrive on a limited variety of foods, and to use fat for fuel.

Ketosis Kept Early Humans Alive when Hunting Failed

The Hadza and Kung bushmen of Africa who hunt with bows and arrows are living examples of the fast and feast cycles that our early ancestors adapted to. These bushmen get meat on only half their excursions into the savanna in search of wild game.

All humans, including adept hunters like these bushmen, are relatively slow, and much weaker than the large prey we once depended on for sustenance; think of Woolly Mammoths, other primates, bears, or powerful herd animals like wildebeests.

What allowed humans to dominate these faster and stronger animals, and to multiply our species was our superior intelligence. Like the bushmen of today, our ancestors made bows and arrows, set traps, and herded animals into optimal hunting zones by strategically setting fires.

Trapping, skillfully wielding tools, and cooperating with other humans all require sharp focus and clear, sustained mental energy. It would have been impossible for a glucose-starved brain to take down a mammoth.

That’s where ketosis comes in. The early humans who couldn’t go into ketosis, whose brains and bodies were not able to use fat for fuel, had their genetics literally, and figuratively, stomped out.

Evidence for Meat-Centered Diets Among Hunter Gatherers

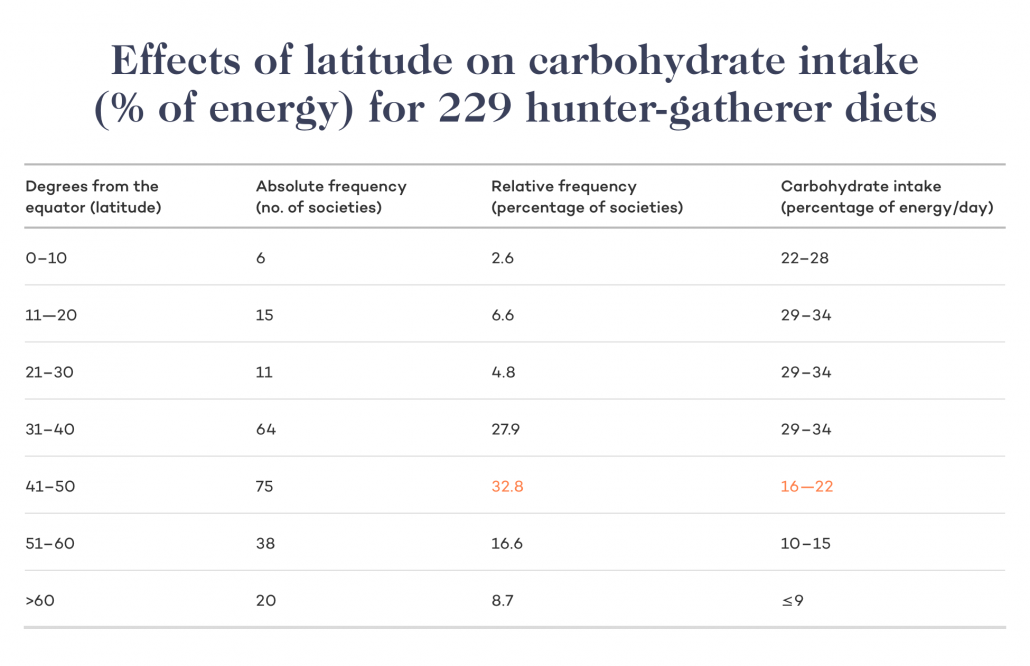

Contemporary research into the two hundred and twenty-nine remaining hunter gatherer tribes show that a low carbohydrate and high-fat diet is the most common.

A 2011 study by Ströhle and Hahn, found that 9 out of 10 of the diets of hunter-gatherer groups had less than a third of calories coming from carbohydrates. These percentages reflect that most hunter-gatherer societies rely on an animal-based diet.

The term “animal” is more accurate than “meat”. Hunter gatherers favor certain parts of the carcass and often discard other edible parts. It is common for traditional peoples to discard the leanest muscle, what today we’d call the tenderloin–the part most modern humans think of as meat.

Fat and Organ Meats

An example of tribal peoples selecting for fat and organ meats is documented by Weston A. Price, a dentist who traveled the world on a quest to study the diets of non-Westernized populations.

In his book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, Price observed the following practice among Indians living in the Northern Canadian Rockies:

“I found the Indians putting great emphasis upon the eating of the organs of the animals, including parts of the digestive tract. Much of the muscle meat of the animals was fed to the dogs. … The skeletal remains are found as piles of finely broken bone chips or splinters that have been cracked up to obtain as much as possible of the marrow and nutritive qualities of the bones.” Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, 6th Edition, page 260.

The Indians Price observed threw away the lean muscle meats and ate only the organ meats and bones, which are higher in fatty -acids, essential minerals, and vitamins.

Price took samples of these native animal foods back to his Cleveland laboratory for study. There he found that native diets contained at least four times the minerals as the American diet in the 1930s. With the soil depletion that’s occurred over the ensuing decades due to industrial agricultural practices along with the proliferation of more processed foods, this discrepancy is likely to be much higher today.

Among the traditional people Price studied, he discovered that they prepared their supplementary grains and tubers with techniques of soaking, fermenting, sprouting, and sour leavening, increasing vitamin content and mineral availability.

Animal Fat Helps the Body Absorb Vitamins and Minerals

The biggest health gap between native groups and modern western groups was revealed when Price analyzed the fat-soluble vitamins of both diets.

Price found that the diets of healthy native groups contained at least ten times more vitamin A and vitamin D than the standard American diet. Vitamins A and D are found only in animal fats, including lard, tallow, butter, eggs, fish oils, and animal parts with fat-rich membranes, especially fish roe, shellfish, and organ meats like liver.

Price found that these fat-soluble vitamins are catalysts upon which the absorption and metabolic use of all the other nutrients depend: protein, minerals, and vitamins.

Without the vitamins found only in animal fats, all our essential nutrients, including protein, vitamins, and minerals, mostly go to waste.

Arctic Explorers Encounter the Ketogenic Diet

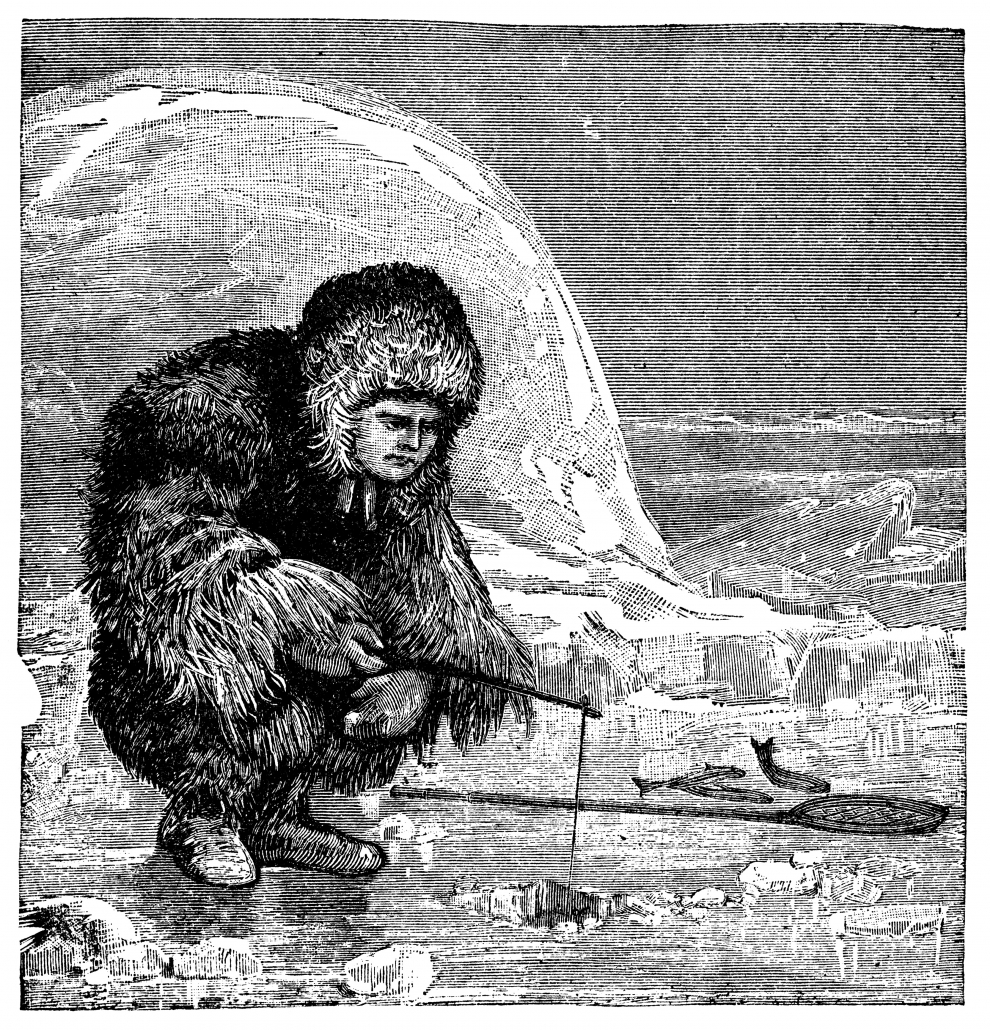

Similar observations about the meat-centered diet were made by another early twentieth-century scientist interested in the link between diet and health in hunter-gatherer populations. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a Harvard-trained anthropologist, went to live with the Inuit in the Canadian arctic. He was the first white man the Mackenzie River band of Inuit had ever seen, and they taught him to hunt and fish with their traditional techniques.

Living exactly as they did, Stefansson ate Caribou, salmon, seal, and eggs. 70-80% of his calories came from fat, and 99% of all his calories came from meat.

Stefansson describes how when eating Caribou, the Inuit most prized the fat behind the eye and the fatty meat around the head, then the organs including the heart, and kidneys.

A caribou kidney is about 50% saturated fat. Just as Price had observed with the American Indians, the Inuit cast the tenderloin to their dogs. They also avoided hunting calves who were lean, selecting older caribou who packed significant fat that could be rendered from their back slabs.

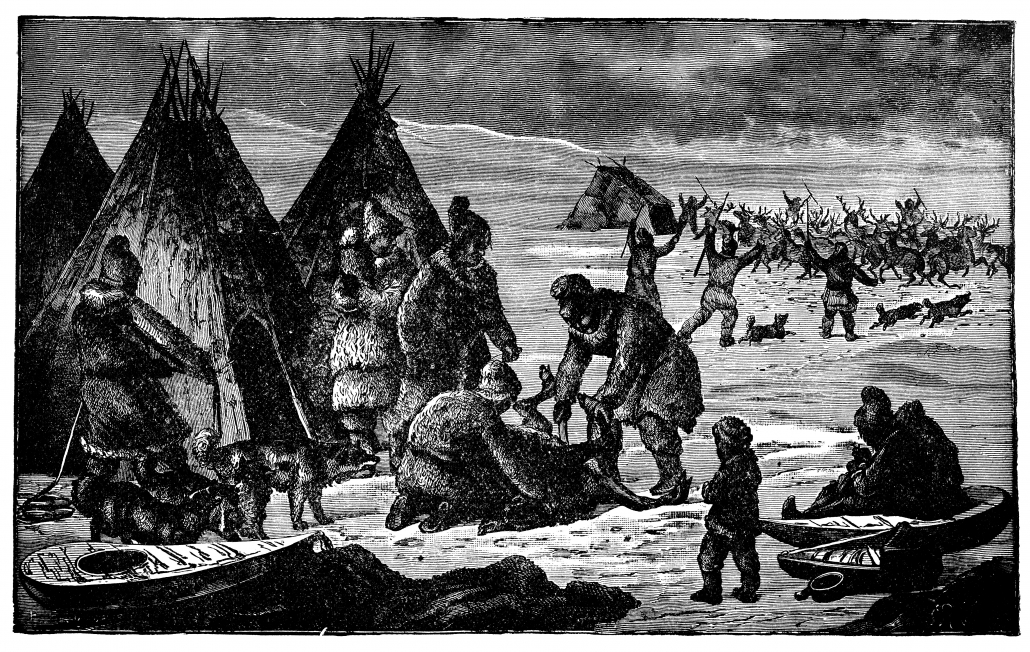

The Schwatka Expedition

A few decades earlier another arctic explorer, Lt. Frederick Schwatka, became similarly acquainted with the hunter-gatherer diet of the Inuit. In 1878 Schwatka’s team headed deep into the arctic to investigate what had happened to a party of 129 men who had disappeared in 1849. The investigation lasted two years, during which Schwatka and his men lived with the Inuit.

Over the first 3000 miles of their journey across tundra by foot and sled they subsisted on the “white man’s” food they brought along. This mean fruit cakes and whiskey. Eventually their supplies ran out. Like Stefansson, they hunted and ate as the Inuit, surviving on an all-meat diet of reindeer, seal, and bear.

An Account of “Keto Flu” from the Lost Journal of an Arctic Explorer

Schwatka’s journals from his expedition leave us with what is perhaps the earliest Western account of what today we commonly referred to as the “keto flu.”

This period of low energy takes place as the human body switches from using carbohydrates to producing ketones from fat for fuel.

“When first thrown wholly upon a diet of reindeer meat, it seems inadequate to properly nourish the system and there is an apparent weakness and inability to perform severe exertive, fatiguing journeys. But this soon passes away in the course of two or three weeks…However, seal meat which is far more disagreeable with its fishy odor, and bear meat with its strong flavor, seems to have no such temporary debilitating effect upon the economy.”

Schwatka’s entry reveals the difference between a low-to-no carb diet and a keto or fat-centered diet.

When he and his men ate lean reindeer meat, the period of adaptation to ketosis was long and difficult. In fact, they were suffering from starvation. Their bodies were metabolizing depleted fat stores–they were essentially eating themselves.

But when they ate the much fattier bear and seal, their bodies were able to turn the ingested fat into ketones from the outset, making the transition much easier.

Though Schwatka’s experiences of an arctic keto diet were hidden in his journal and not discovered until long after his death, Stefansson returned from his Arctic adventure as a boisterous champion of an all meat, mostly fat, diet.

Introduction of Carnivore Keto Diet to the West

In the early 1900’s there was already the stirring of what would become the mainstream American medical establishment’s recommendation against meat and demonization of fat.

Vegetarians were numerous and raw vegetables, particularly celery, were seen as the key to health and beauty. As the saying goes, what’s old is new.

When Stefansson promoted his carnivore diet he was met with hostile disbelief. Doctors feared that an all-meat diet could not provide vitamin C, since the vitamin doesn’t exist in cooked muscle meat. They assumed a vitamin C deficit would lead to scurvy as it had for many fur trappers and frontiersmen who relied on all-meat diets for extended periods.

To prove his detractors wrong, Stefansson and a friend vowed to eat nothing but meat and water for a year.

Protein Poisoning from Lack of Fat

Under the observation of experts from New York’s Bellevue Hospital, Stefansson and his friend fell ill only once during the entire year, and only after experimenters encouraged them to eat only lean meat.

Stefansson describes this low-fat experience as inflicting “diarrhea and a feeling of general baffling discomfort.” This condition has since been dubbed ‘rabbit starvation.’ It occurs in diets low in fat and carbohydrates and high in protein.

To this day, military survival manuals warn against eating rabbits if you find yourself in a situation where you have to subsist by hunting and gathering.

Rabbit starvation is better understood as protein poisoning, and it is due to the inability of the human liver to upregulate urea synthesis to process excessive loads of protein, leading to a whole host of problems, including hyperaminoacidemia, hyperammonemia, hyperinsulinemia, nausea, diarrhea, and even death within two to three weeks.

Not to fear, Stefansson and his friend were quickly cured by a single fat-loaded meal of sirloin steak and brains fried in bacon fat.

After the incident of ‘rabbit starvation,’ experimenters found the ideal ratio to be 3 parts fat to 1 part lean meat, which is not surprisingly the foundation of a ketogenic diet.

Interestingly, and in contradiction to fearful doctors, scurvy and other nutrient deficiencies never materialized. Stefansson and friend’s sterling bill of health is likely because the men ate the whole animal, bones, liver, and brains. This practice is consistent with the diet of the earliest humans and which, as we saw in Price’s studies, contains loads of vitamins and minerals.

Good Health and High Fat Diets among African Pastoral Tribes

Traditional Masai men eat nothing but meat—often three to five pounds each during celebratory meals—blood, and half a gallon of full-fat milk from their Zebu cattle—the equivalent of a half-pound of butterfat.

Likewise, the Samburu people eat on average a pound of meat and drink almost two gallons of raw milk each day during most of the year—equivalent to one pound of butterfat per day! While shepherds in Somalia consume a gallon and a half of camel’s milk each day, also equivalent to a pound of butterfat.

Each of these tribes gets more than sixty percent of their energy from animal fat, yet their mean cholesterol is only about 150 mg/dl (3.8 meq/l), far lower than the average Western person.

In the 1960’s prominent doctor and professor, George V. Mann studied the Masai as an example of a population that thrived on a high-fat, low-carb, and no-vegetable diet. Mann’s life work was aimed at confronting what he called the “heart mafia.” These were a group of influential figures and institutions in the American medical establishment who built their careers creating and defending erroneous links between the consumption of dietary fat, high cholesterol, and an increase in heart disease.

Mann found that despite the Masai’s high-fat diet, their blood pressure and weight were about 50% less than they were for Americans and that they experienced almost no heart disease, cancer, or diabetes—the so-called diseases of civilization.

The Masai’s Stellar Health Linked to High Fat Diet, not Genetics

Mann’s detractors asserted that African tribes like the Masai were genetically adapted to a high-fat diet. However, a study of Masai people who lived in the Nairobi metropolis showed this to be false.

The Nairobi Masai ate considerably less fat, which would suggest to researchers taking the genetic inheritance perspective, that their cholesterol should be even lower than their brethren still living in the countryside. Yet the mean cholesterol of the Nairobi Masai was 25 percent higher.

What’s more surprising is that the markers of physical health and absence of disease that Mann found in the rural Masai, persisted into old age.

Mann’s findings fly in the face of the prevailing wisdom of the Western medical establishment that as humans age, cholesterol and weight, along with instances of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, all inevitably increase.

Animal-Centered Diets and Longevity in American Indians

Mann’s work with the aging Masai reflects the earlier observations of Ales Hrdlicka, a doctor and anthropologist, who, between 1898 and 1905, surveyed the health of Native American populations in the American Southwest.

Studying Native American elders who lived most of their lives on a diet based on meat from wild game, especially buffalo, before their traditional ways of life were destroyed, Hrdlicka found the population to be in incredibly good health.

Malignant diseases were extremely rare, as was dementia and heart disease–he found only 3 cases out of the 2000 people he surveyed. He also found that there were many more centenarians among the Native Americans (224 per million men, and 254 per million women) compared to the whites (3 per million men, and 6 per million women).

Stefansson, Mann, and Hrdlicka’s observations of hunter-gatherer and non-Western populations thriving on diets based on animal fats are only a few examples among many from our anthropological record.

These findings beg the question of whether agriculture was a true step forward for human health? And the answer appears to be a resounding No!

Pitfalls of the Agricultural Revolution

In leaving behind our hunter-gatherer ways of life and diets we became dependent on crops, mostly grains. Our diets became far less nutritious and diverse.

Subsisting on the same grain, i.e. carbohydrates, day in and day out, lead to a huge uptick in cavities and periodontal disease that we don’t find in hunter-gatherers. Tending to crops all day was more laborious and time-consuming than hunting and foraging.

This surplus of consistent calories from grain caused populations to boom, creating more mouths to feed. When disease struck or a crop failed, huge portions of the population were afflicted. Suffering from iron, fat, and protein deficiencies, people shrunk, both in terms of their brain size and physical stature.

“It is not as if farming brought a great improvement in living standards either. A typical hunter-gatherer enjoyed a more varied diet and consumed more protein and calories than settled people, and took in five times as much vitamin C as the average person today.”-Bill Bryson

The Sad Legacy of Agriculture

Today we see the sad legacy of our dependence on agriculture and a diet dominated by carbohydrates. It’s ensconced in the misconceived recommendations of the mainstream medical establishment. It’s trumpeted by so-called food gurus like Michael Pollan, whose infamous statement, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants,” encompasses everything that’s wrong with the way we eat.

A better rallying cry, which echoes those of the vast majority of our human ancestors, is the exact opposite: Eat fat. Not too little. Mostly from animals!

Yet we find ourselves in the same predicament: Study after study is bearing out the same sad story. Inflammation and stress-related diseases like diabetes, heart disease, mental disorders, asthma, and autoimmune diseases like IB and ulcerated colitis are skyrocketing among both young and old populations.

This increase is a direct result of modern diets and lifestyles. Our genes and physiology, which are almost identical to those of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, preserve core regulation and recovery processes. Yet nowadays, our genes operate in internal and external environments that are completely different from those we were designed for.

The Takeaway

Of course, we cannot go back to our hunter-gatherer lifestyle, but we can integrate into our modern lives the natural wisdom of how humans evolved to eat.

One way to look at our predicament is through the lens of the zookeeper paradox. A zookeeper’s job is to ask if their animals are well adapted to the food and environment that is artificially provided for them.

We humans are animals. Our modern lifestyles and diets are artificial compared to the world we evolved in for hundreds of thousands of years. You could say we are our own zookeepers.

When we look at the historical evidence alongside contemporary medical data, it becomes glaringly apparent that we are doing a terrible job of caring for ourselves as a species.

By traveling back in time through our dietary evolution, we can learn to better care for ourselves, beginning with the food we eat: Animal meat, especially fat, is the cornerstone of a diet we humans are evolved to thrive on.