We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

The Amber O’Hearn “Lipivore” Carnivore Diet

L. Amber O’Hearn M.Sc is a Carnivore diet thought leader who popularized the term “lipivore” to describe the evolutionary human adaptation to a high-fat low-carb meat-centered diet.

O’Hearn is a data researcher, founder of CarnivoryCon, an annual conference dedicated to the carnivore lifestyle, and the author of Eat Meat. Not Too Little. Mostly Fat.

Like Dr. Kiltz, O’Hearn has experimented with low-carb and ketogenic diets for decades, eventually finding her way to carnivore.

O’Hearn first came to carnivore while exploring treatments for a mood disorder that was originally diagnosed as treatment-resistant depression and rediagnosed as bibolar disorder.

O’Hearn found relief with the carnivore diet and has been practicing the plant-free, all-meat lifestyle since 2009.

By definition, a carnivore diet food list calls for eating nearly all meat with some exceptions for dairy. For most modern people coming from a standard American diet, “meat” means muscle meats AKA protein.

However, both Dr. Kiltz and O’Hearn believe that thinking of meat as protein is incorrect: the optimal food for humans is animal fat, with some protein, and very low to no carbohydrates. Fat is the most important nutrient in the human diet.

Table of Contents

Humans As Lipivores: Fast Facts

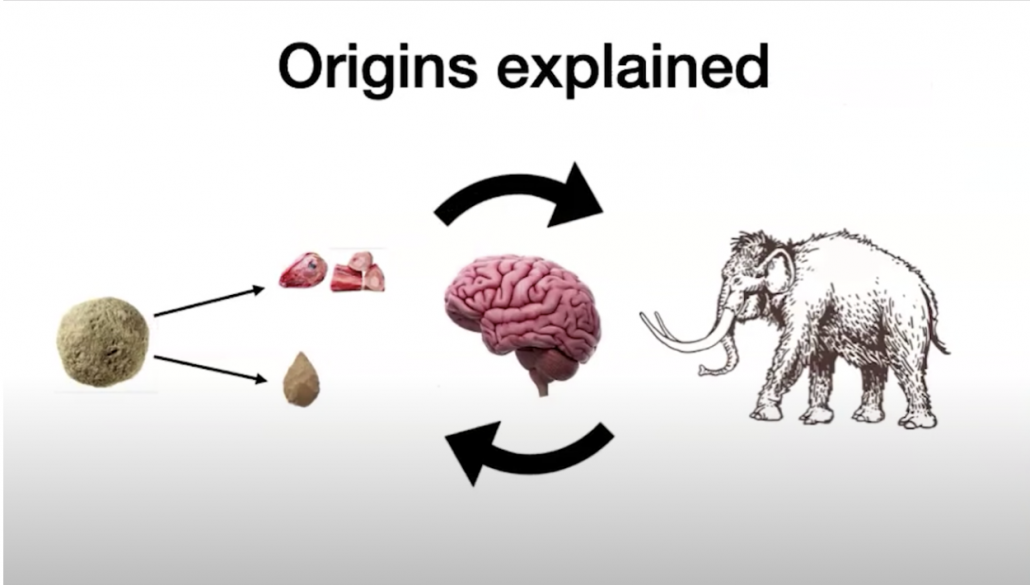

O’Hearn draws from numerous lines of archaeological and nutrition research to offer a compelling argument that humans evolved our enormous brains–our most human trait–by first scavenging fat from megafauna before eventually hunting these large fatty animals. O’Hearn supports her argument with evidence including:

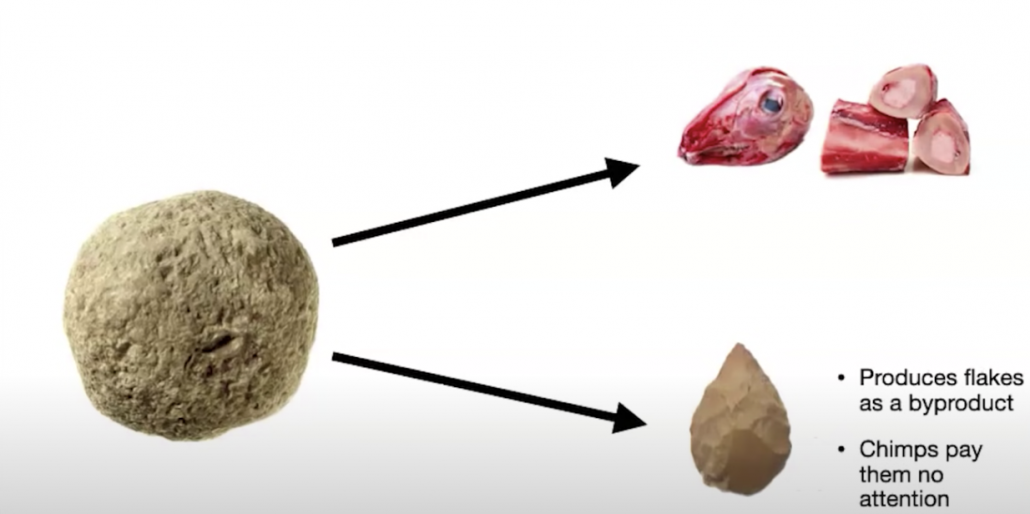

- Blunt percussion tools were the first tools of record used by human beings

- Early humans used percussion tools to break open skulls and bones from large animals killed by other predators

- Scavenging fatty marrow and brains directly fueled the rapid growth of the human brain

- Humans have a unique propensity to store fat on our bodies

- Unlike other predators, humans can easily enter ketosis during mundane, calorically replete states, not just starvation states like other mammals.

Let’s explore Amber O’Hearn’s argument in greater depth. The images here are borrowed from O’Hearn’s youtube video ‘The Lipivore: What is Fat for?’ which you can view here:

The view that a diet of fatty meat is the ideal approach to human nutrition is supported by evidence that our caveman ancestors were hyper-carnivorous apex predators for nearly 2 million years [1].

Yet, in our high-carb society, we use meat incorrectly, or incompletely, as a protein. Even carnivore dieters make this mistake.

In the context of an ancestrally supported carnivore diet, “meat” means animal fat and very fatty keto meats.

Let’s take a look at each step of O’Hearn’s argument.

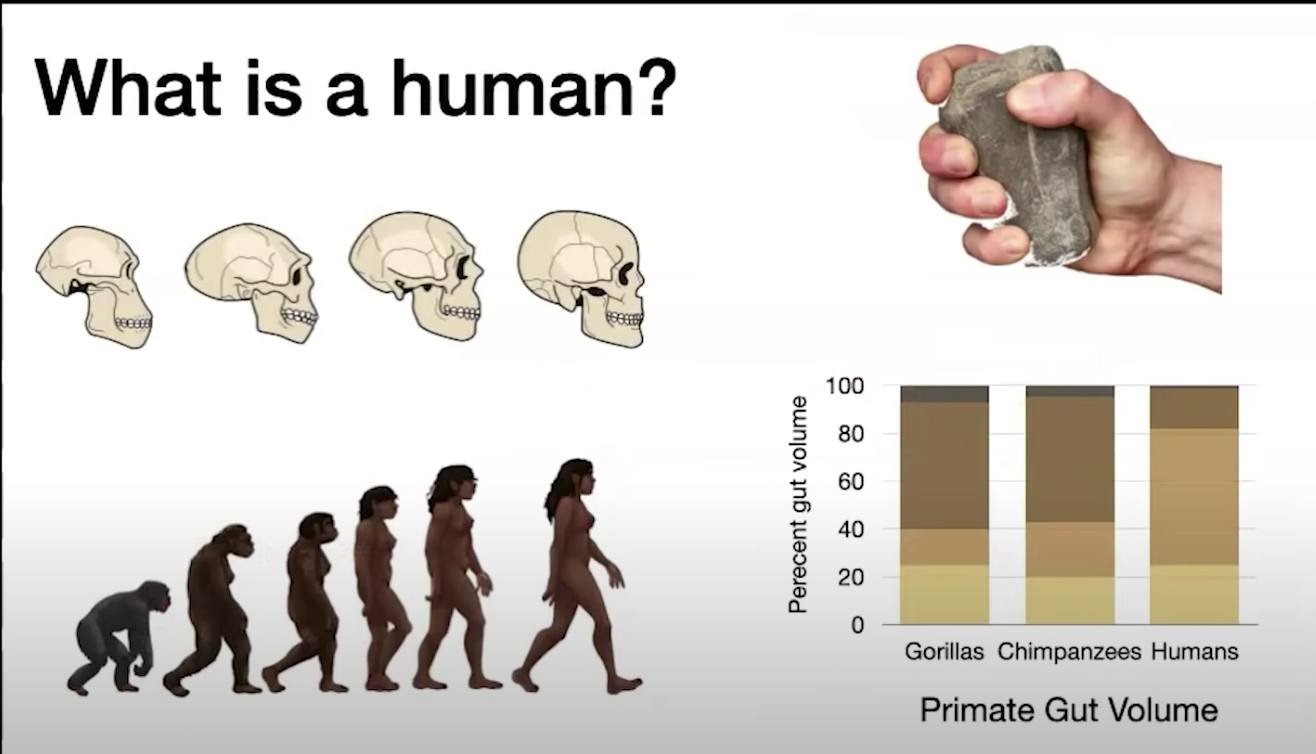

What Sets Humans Apart from Apes?

There are many aspects of our human bodies that set us apart from our closest primate relatives.

- We have huge brains

- We walk upright

- We have a precise, powerful hand grip

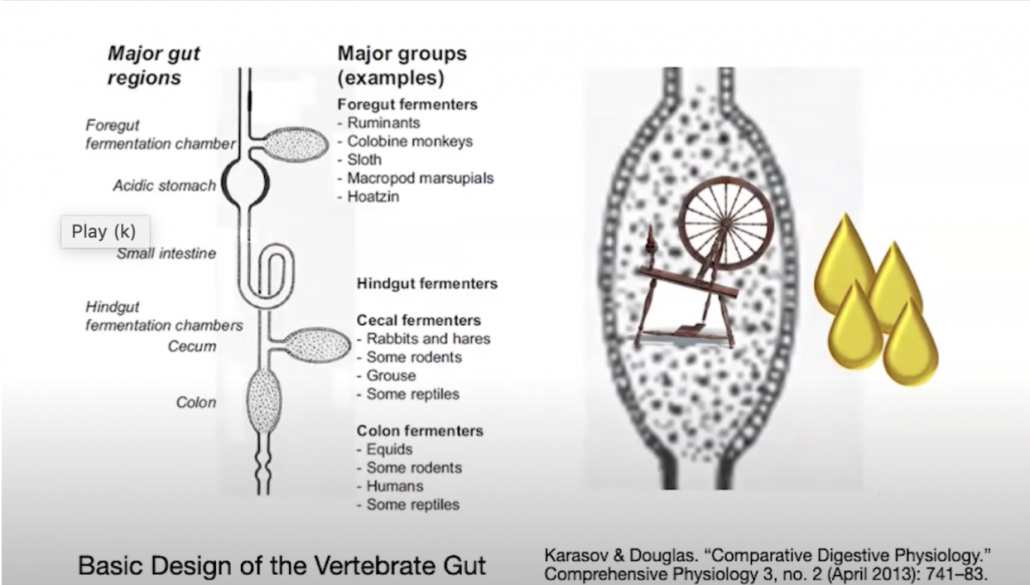

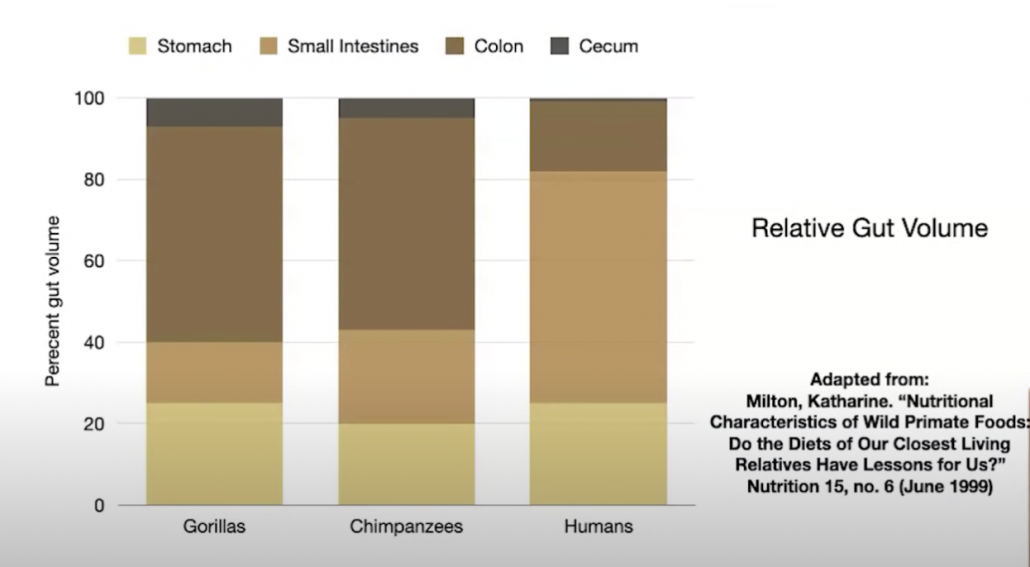

- We have a short digestive tract

- Our digestive system is based on hydrochloric acid and large small intestines with less fermentation compared to the very large large intestines and colons of other primates which ferment their foods

- Humans carry exceptionally high body fat

O’Hearn argues that each of these traits are deeply interconnected with our evolutionary adaptation for prioritizing dietary fat.

Her hypothesis is that humans are not only specialized for eating animals foods, but specifically for eating animal fat.

Biases Against Lipivore Carnivory?

O’Hearn points out that everyone grows up thinking that their inherited lifestyle is normal and every alternative is strange and abnormal.

Modern medicine and nutritional science have grown up in a grain-based society. Therefore biases of modern medicine and how to treat our physiology center around a high carbohydrate diet.

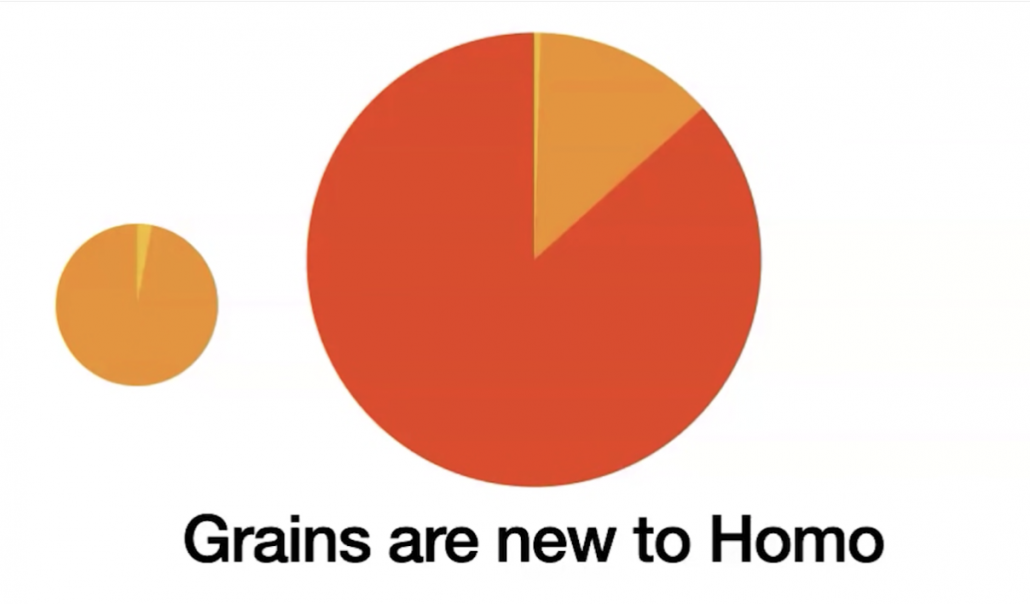

But grains have arrived very recently on the dietary scene. Anatomically modern humans have only had grains for around 7,000 years–just a sliver of our time on earth.

Looking back even further to the beginning of the genus “homo” from which homo sapiens evolved, the sliver becomes even smaller.

So the question becomes, what were our ancestors eating for that vast majority of time before grains?

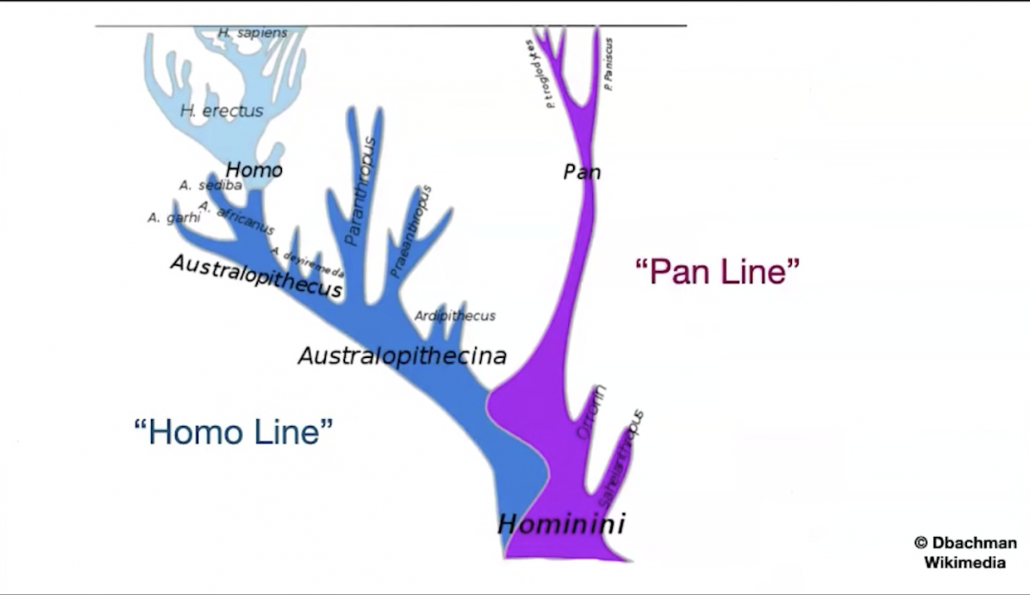

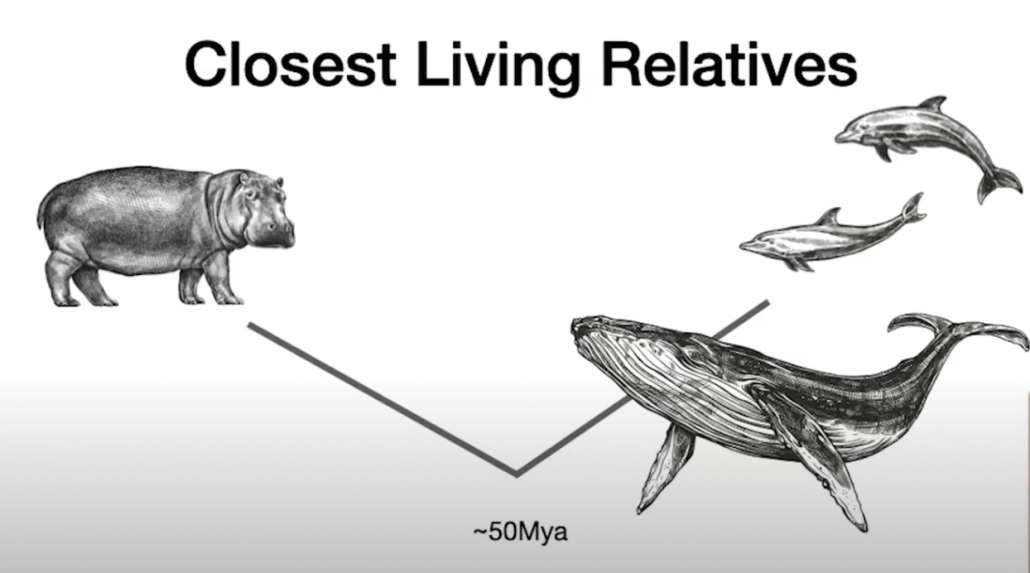

O’Hearn points out that it is a mistake is to think of our history as modeled by our closest living relative–the chimpanzee.

Our last common ancestor with chimpanzees was over 5 million years ago.

People like to emphasize the similarities between the ‘homo’ line and the ‘pan’ line, but the differences are perhaps more important when it comes to understanding our adaptations to nutrition.

As an analogy, O’Hearn uses the hippopotamus and its closest relative, the dolphin. Where hippos are herbivores and dolphins are carnivores.

Human vs. Primate Hunting and Eating of Prey

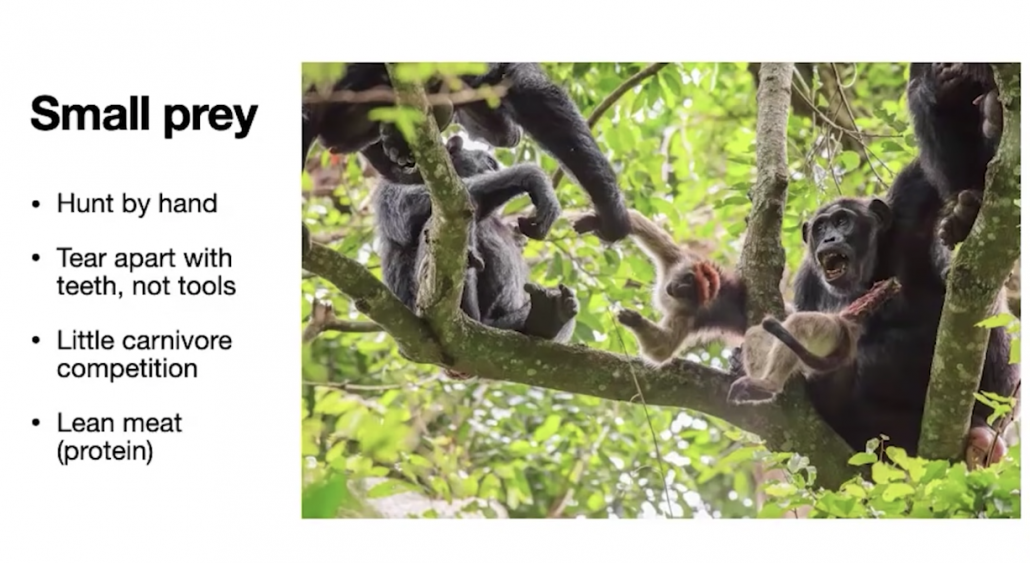

Primates supplement mostly plant-based diets with small prey. They hunt by hand and eat using teeth, rather than with tools.

With most of their hunting done in the forest, and often in the canopy, they don’t have carnivore competition. The small prey they consume provides high-quality protein and micronutrients. But human nutritional evolution followed an alternative path and came to a different conclusion.

For most of human history, Homosapiens:

- hunted very large prey (megafauna)

- hunted in grasslands competing with other large predators

- used flake stone weapons and butchering tools

- hunted large animals provided large deposits of fat

- ate larger mammals that had more fat proportional to their mass

Old vs. New Narrative on Human Dietary Evolution

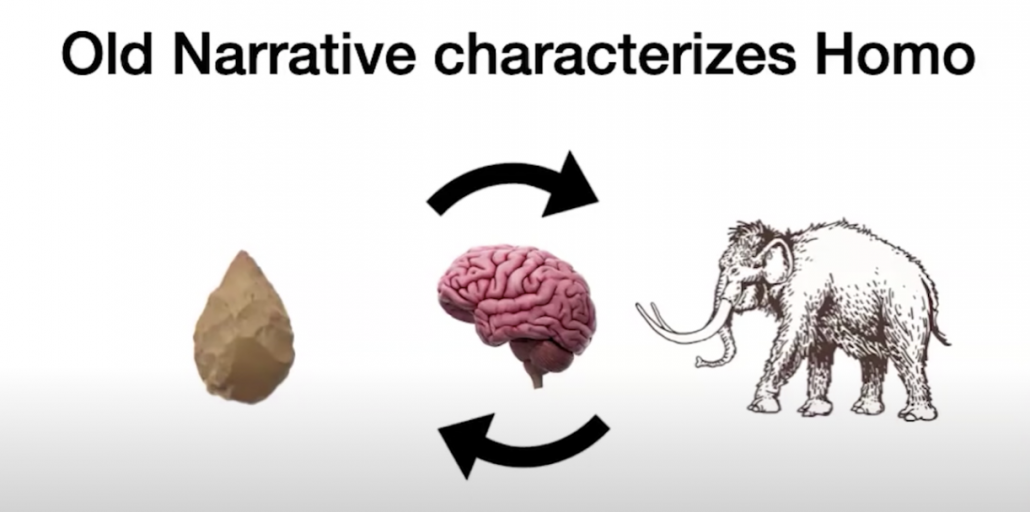

The old narrative on the dietary evolution of humans holds that humans invented stone tools that allowed them to hunt large game. In turn, the nutrient-rich meat of large animals fueled the rapid growth of the human brain.

The new narrative asks the question–how could we be smart or motivated enough to devise a complex tool if we didn’t already have an experience of the nutritional value of large prey? Early humans wouldn’t need these tools for small prey.

Hunting large prey requires different techniques, tools, and physical adaptations than small prey.

It makes more sense to tell the story of eating large prey, beginning with the tools that we already had: Percussion tools. All you need in order to use these tools is to grip and smash.

Interestingly, researchers believe that the activity of gripping and smashing is the evolutionary force that selected for the particular shape and strength of human hands.

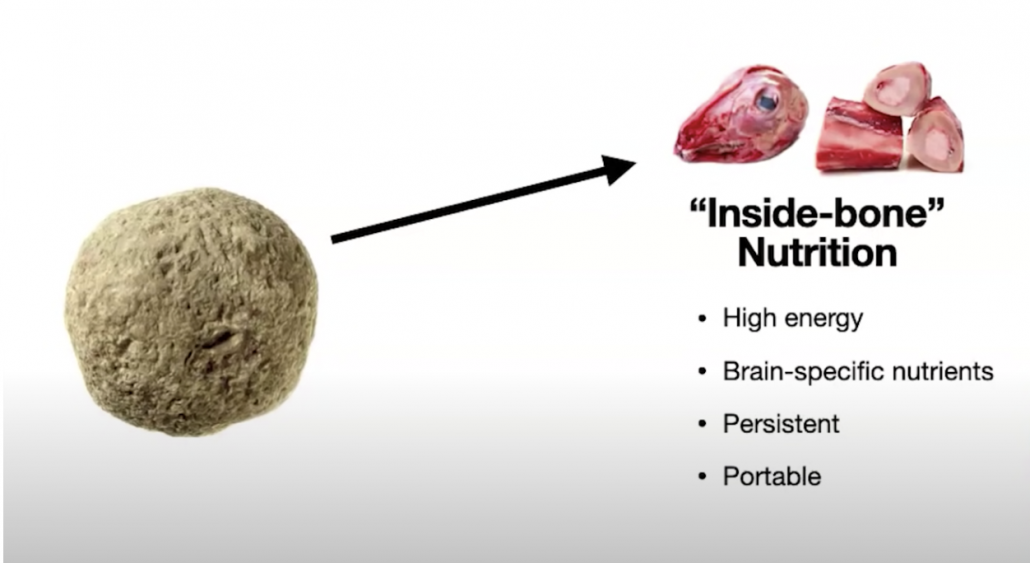

Chimps use stones to break open nuts. But going all the way back to the beginning of the “homo” line, Australopithecus used stones to break open bones and skulls–the parts left over from kills that other carnivores can’t access with their teeth and claws.

Within bones and skulls are high-fat meats loaded with brain-specific nutrients.

The meat within bones is also sheltered from bacteria, so it lasts longer. This allows it to be transported to a safer place to consume–a development corresponding with the early hominid adaptations allowing our ancestors to carry heavier loads further distances.

Percussion tools give off flakes as a byproduct of their use. So the exact tool that would help early hominids eventually hunt and make use of meat was dropping into their laps.

So the new, more plausible and parsimonious narrative is that early humans were already relying on the bone-meats of large animals scavenged from carcasses. Then the tools we’d later use for hunting large prey arrived as a natural byproduct of bone-meat processing.

This development happened independently of small-prey hunting. Large prey hunting comes exclusively through the scavenging pathway.

This sequence suggests that humans have inherited adaptations to eating fatty meat from larger animals very early in hominid development.

Therefore the homo-predatory pattern is “fat-seeking”. Fat is responsible for human brain growth, intelligence, use of tools, and the consequent focus on hunting meat.

Facultative “Lipivore” Carnivore vs. Herbivores and Carnivores

Herbivores and standard carnivores make use of their primary nutrients in ways that humans cannot.

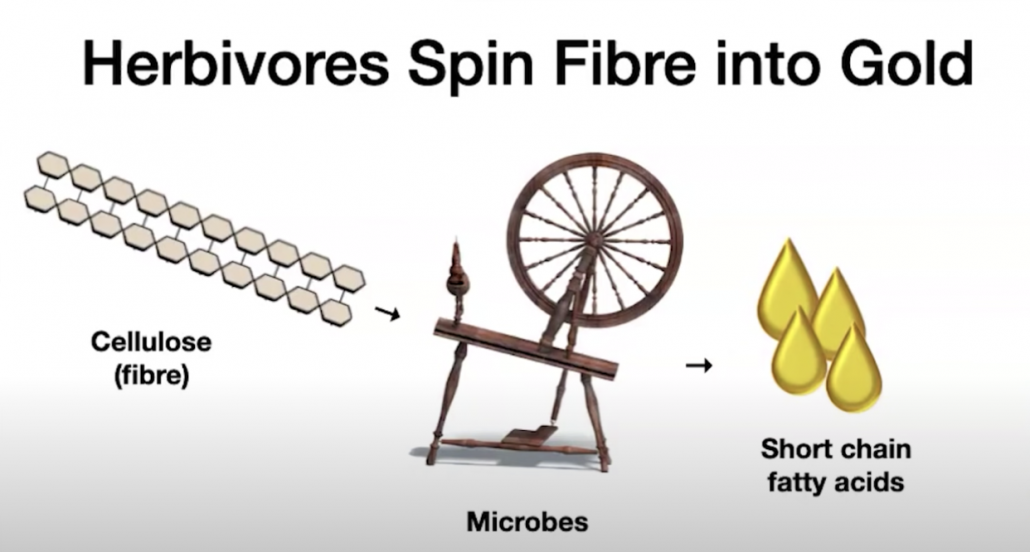

Herbivores ferment plant fibers into fatty acids. They can do this because parts of their digestive tract house microbes that digest fiber into short-chain fatty acids.

Fermenting plants into fat requires a much larger and different gut than humans have.

Our closest relatives have more than ½ of the digestive tract devoted to the colon and cecum. Whereas humans have a much smaller colon and very small cecum.

These physiological changes demonstrate a species-wide commitment to obtaining most of our nutrients from sources that are not fibrous–i.e. Not plant foods.

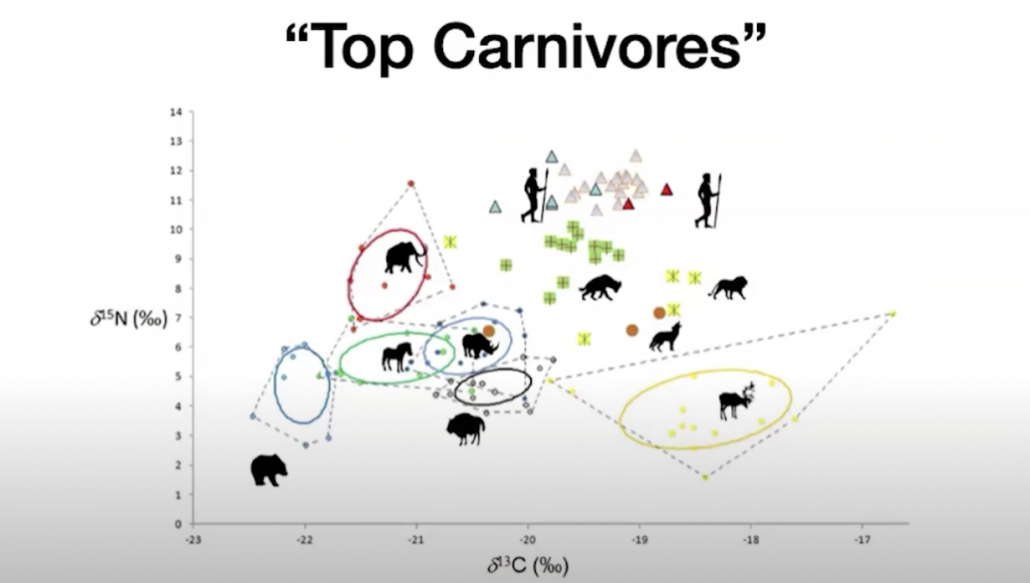

Humans are Apex Predators

In support of the argument that our ancestors consumed large mammals, Amber O’Hearn references bone isotope analysis. These studies look at chemical traces that accumulate in bones when one creature eats another.

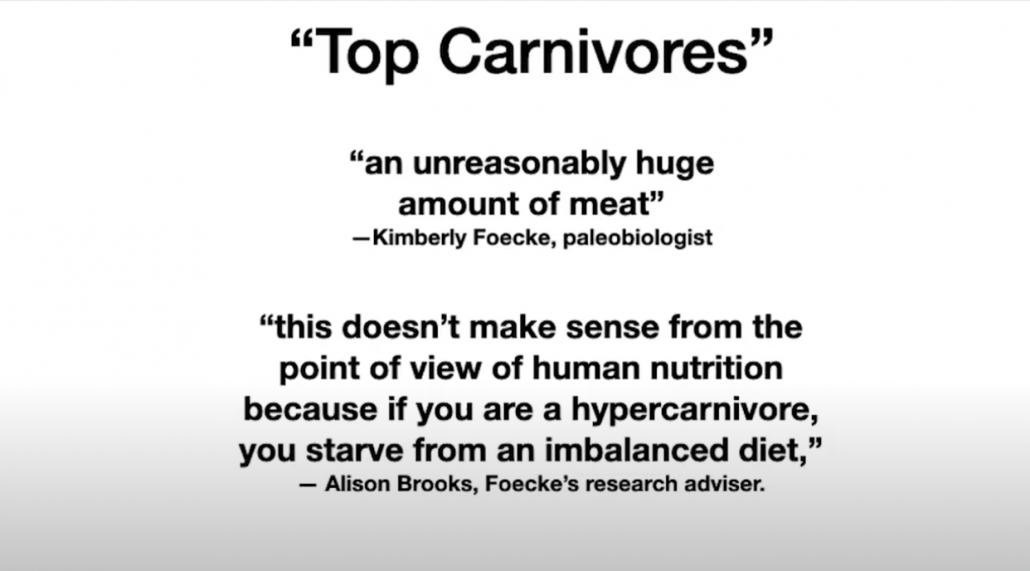

Isotope analysis tells us that early humans ate very high levels of meat, including the meat of other carnivores. Our ancestors were at the top of the food chain, AKA apex predators consuming large prey.

Returning to the notion that our immediate environment biases our views, modern nutritional researchers with a plant-based view can’t make sense of the findings in these isotopes. The idea that humans ate mostly meat doesn’t fit into their “humans as omnivores” narrative.

Here’s an example:

The idea that humans need a “balanced” diet in order to obtain sufficient nutrients makes sense only if you think of meat as just protein.

In fact, it is possible to starve when eating mostly muscle meat. This phenomenon is called rabbit starvation.

Historical records, like the one above from arctic explorer Vilhalmur Steffanson, show us what happens to people who rely on small prey that has too much protein relative to fat in their diet.

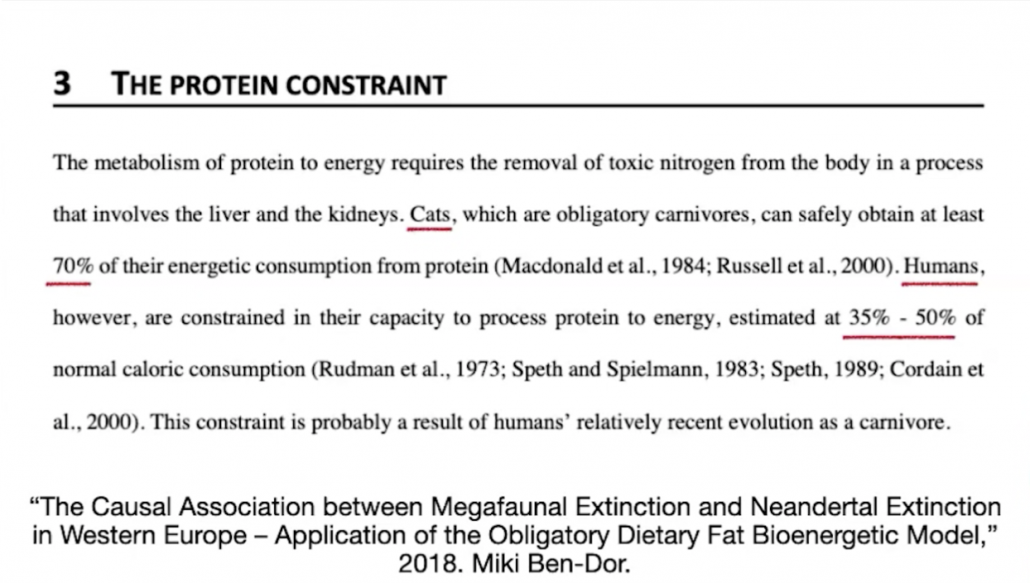

Protein poisoning can result when getting between 35%-50% of your calories from protein.

Too much protein causes your liver to lose the ability to upregulate urea synthesis needed to process high protein loads.

Symptoms of protein poisoning include hyperaminoacidemia, hyperammonemia, hyperinsulinemia nausea, diarrhea, and rare cases, death [32].

But early humans who ate a ton of meat didn’t get protein poisoning–otherwise, we wouldn’t be here! And this is because “meat”, to a large extent, means fat from large mammals.

Humans derive satiety and sustenance primarily from fat. We see this preference reflected in the habits of modern hunter-gatherer tribes who often discard game that is too lean.

Compared with humans, other carnivores have much higher protein tolerance. Cats, for instance, can get 70% of their energy needs from protein because their bodies are designed to synthesize it into glucose to feed their brains.

O’Hearn and others believe that the human transition to carnivory drove the mass extinctions of mega fauna–the animals with the optimal proportions of fat to protein for our bodies.

The smaller animals we’re left with now are those that were too lean to bother hunting so aggressively. These smaller animals also have a shorter gestation period than megafauna, which couldn’t reproduce fast enough to replenish their populations.

Fat or Carbs?

So now we’ve seen the physiological limits of obtaining nutrients of fiber and protein. That leaves us with carbs and fat.

Some nutritionists suggest that we made up the remainder of our caloric needs by consuming underground tubers. However, humans didn’t have fire for cooking tubers until 200,000 years ago, which is too late in our evolution to suggest that carbs from tubers contributed to the rapid growth of our brains.

Furthermore, tubers have high levels of plant toxins and antinutrients, necessitating intensive processing, and even then resulting in possible health issues.

Humans are Very Fat Animals

Another key to O’Hearn’s view on humans as lipivores is how fat we are as a species.

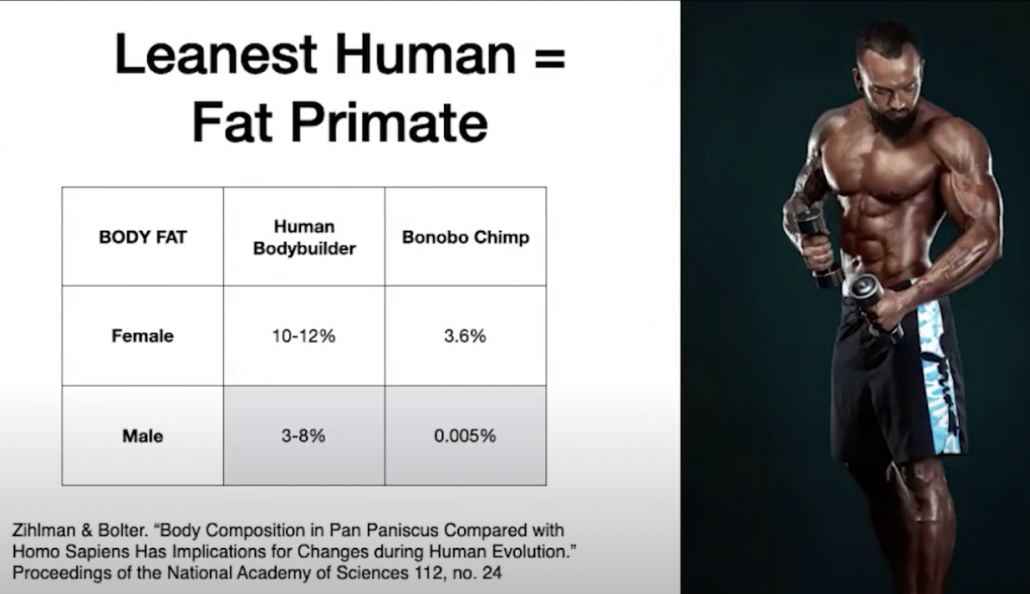

When compared to other primates, even lean people are much fatter.

For example, the leanest version of a human is a male bodybuilder, who on average has 2-3 times more fat than other primates.

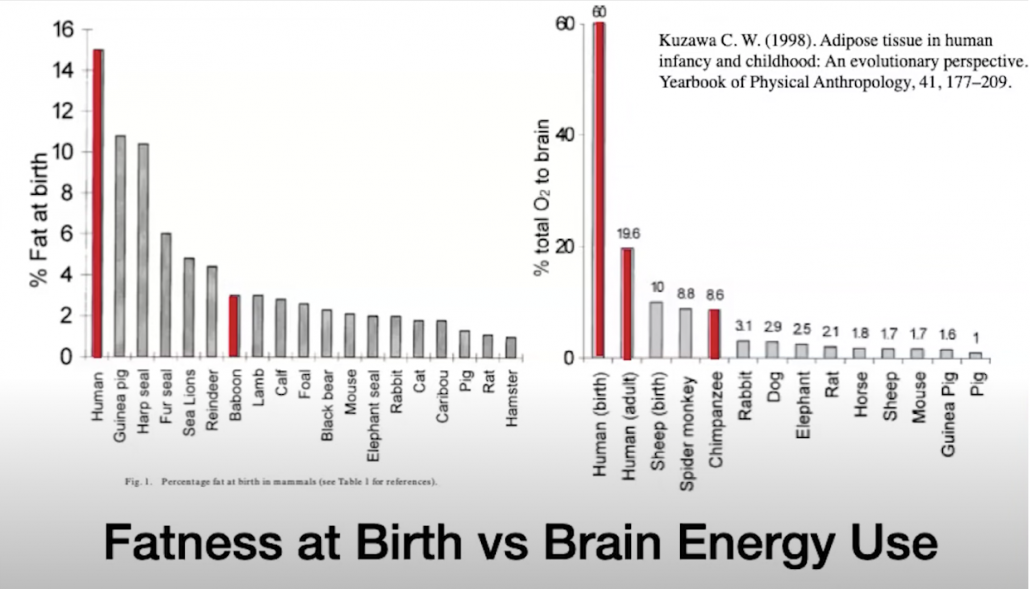

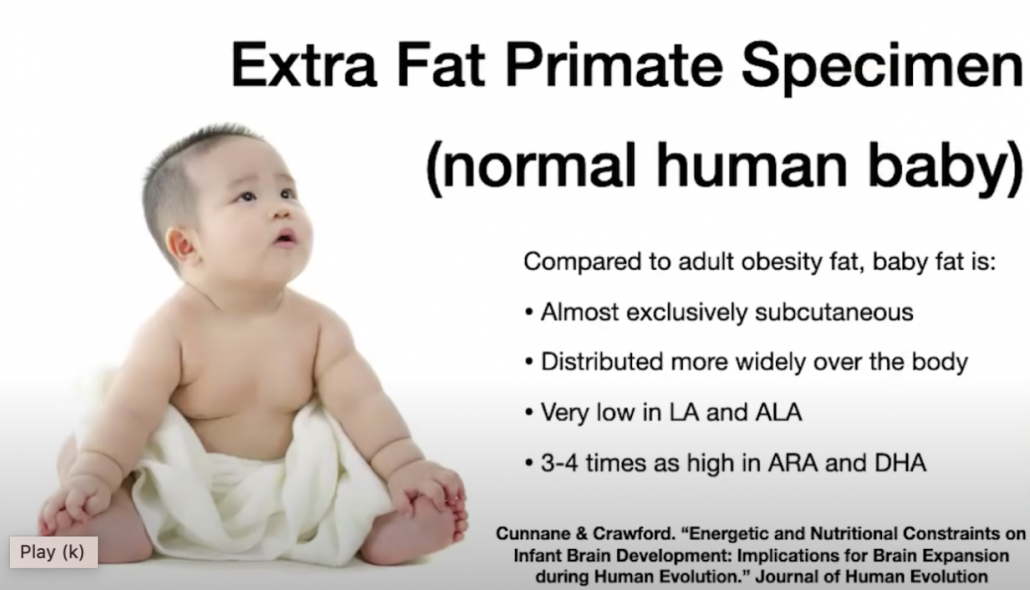

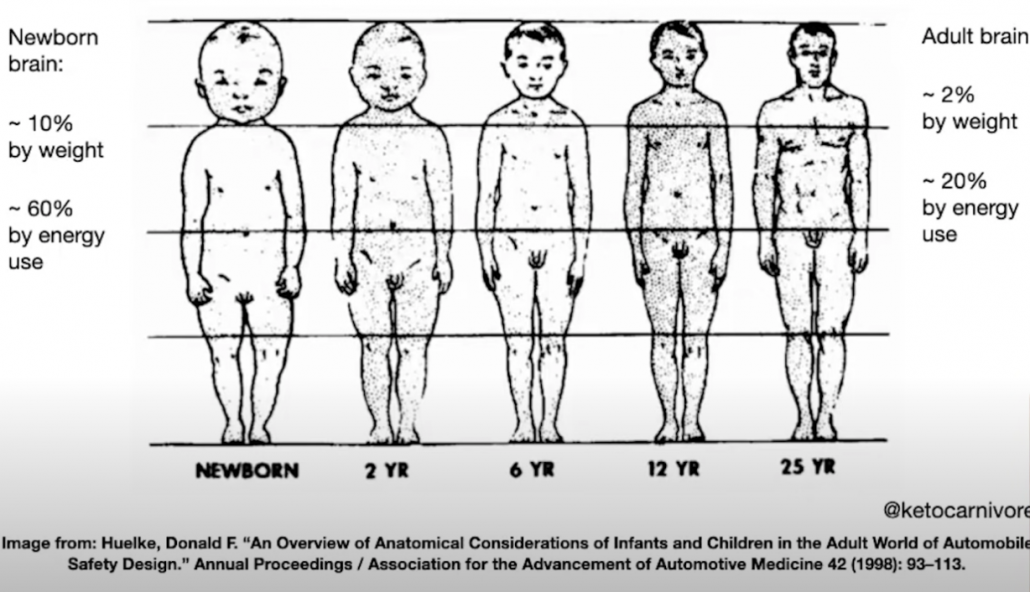

Let’s turn next to human babies, who are notoriously fat, which is not the case for other primates, whose infants are very lean.

The fatness of babies at birth allows the body to turn that abundance of fat into fuel for the baby’s large and rapidly growing brain.

Humans of all ages also have more fat and a different fatty acid profile than most other mammals.

Human babies even outdo baby seals when it comes to fatness. While chimps come in at only 3% fat.

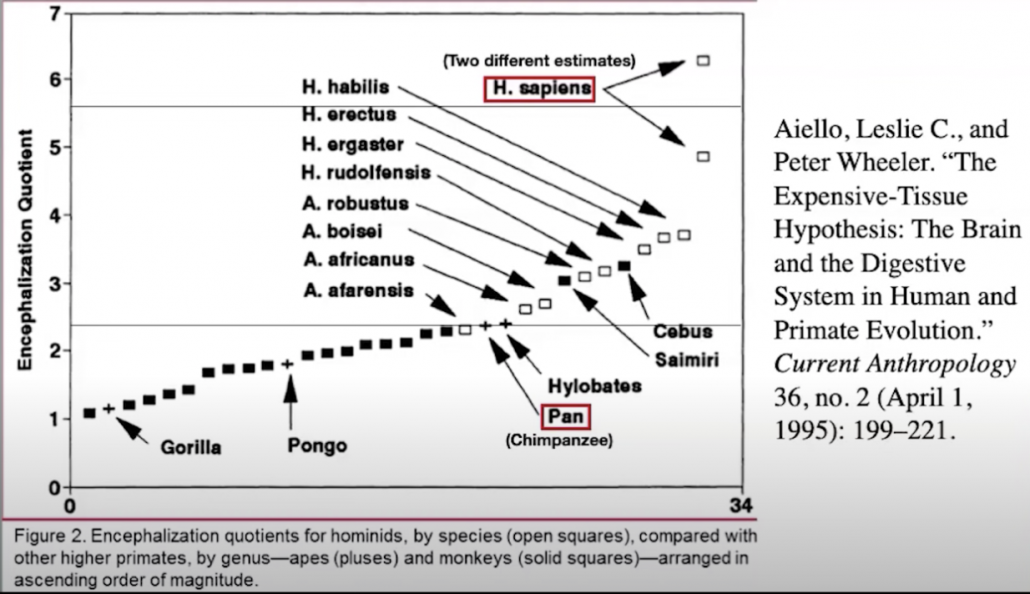

One way to explore the idea that the fat of babies is intended to fuel massive human brains is to look at the encephalization quotient for primates. This quotient measures how big an animal’s brain is relative to their bodies.

The human brain is 2.5 times as large as a chimpanzee brain. This echoes our fatness relative to chimps, again suggesting that fat is our brain’s primary fuel source.

The brains of babies are bigger compared to their bodies than adults. More than half of a baby’s energy goes to running their brain.

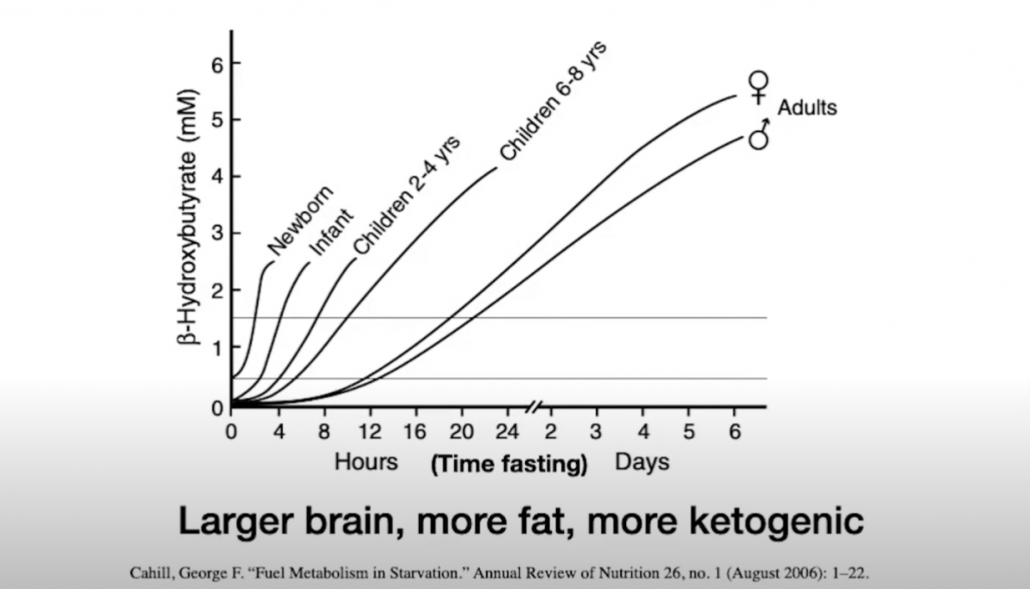

Not only do babies have larger brains compared to their bodies and more fat, babies are more ketogenic than adults.

Amber O’Hearn hypothesizes that the non-babies in the study above are already eating something non-ketogenic, and would therefore have higher baseline ketone levels if consuming an ancestrally congruent high-fat low-carb diet.

Nevertheless, babies do produce ketones better than adult humans, and adult humans are better at producing ketones than other species.

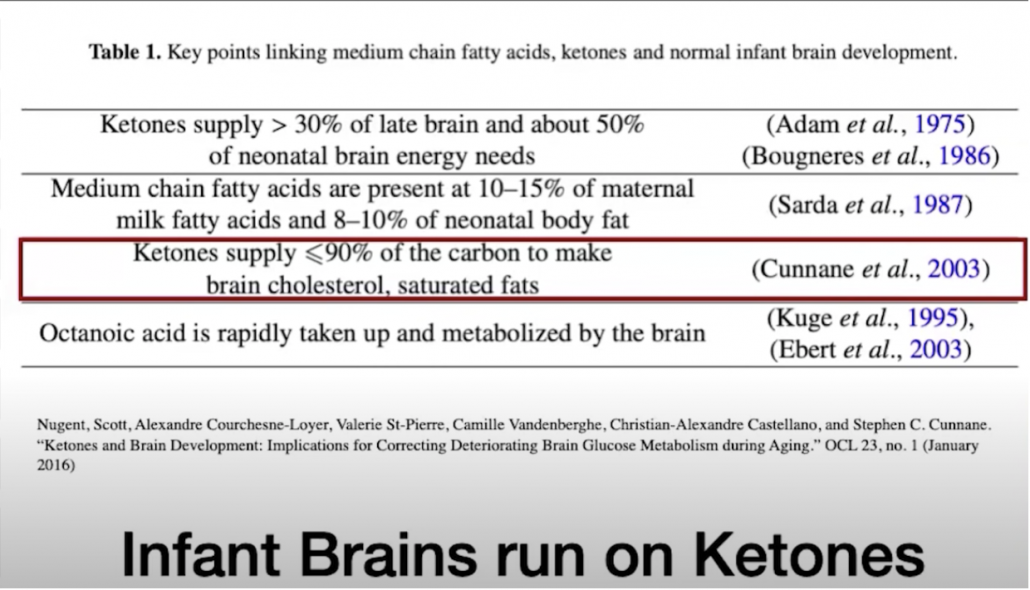

Ketones are energy molecules produced from the metabolization of dietary fat and body fat. And they matter because they support infant brain development.

O’Hearn references studies showing that medium-chain fatty acids that supercharge the formation of ketones are present in breastmilk and infant body fat.

Furthermore, O’Hearn points out that the brain is essentially made by ketones. Ketones act like a transport form of fat that crosses the blood-brain barrier to construct the material of the brain out of cholesterol and other fatty acids.

Ketosis as Stable Adaptation or Response to Starvation

In other species ketosis–the elevated presence of ketones in blood–is an adaptation to starvation. This has led critics of high-fat low-carb diets to suggest that ketosis only occurs when our bodies are in a calorically stressed state, and is therefore unhealthy in the long term.

But humans are unique among species (birds, bears, camels, felions, cetaceans etc) as the only animals that can get into deep ketosis when our caloric needs are met and with as much as double our protein needs.

Amber O’Hearn references studies showing that rats produce enzymes that allow the brain to use ketones only when starving.

But for humans, these same enzymes are always available and starvation states do not elevate them. The brain is always ready for ketones, and it will take up as many ketones as are circulating in the blood.

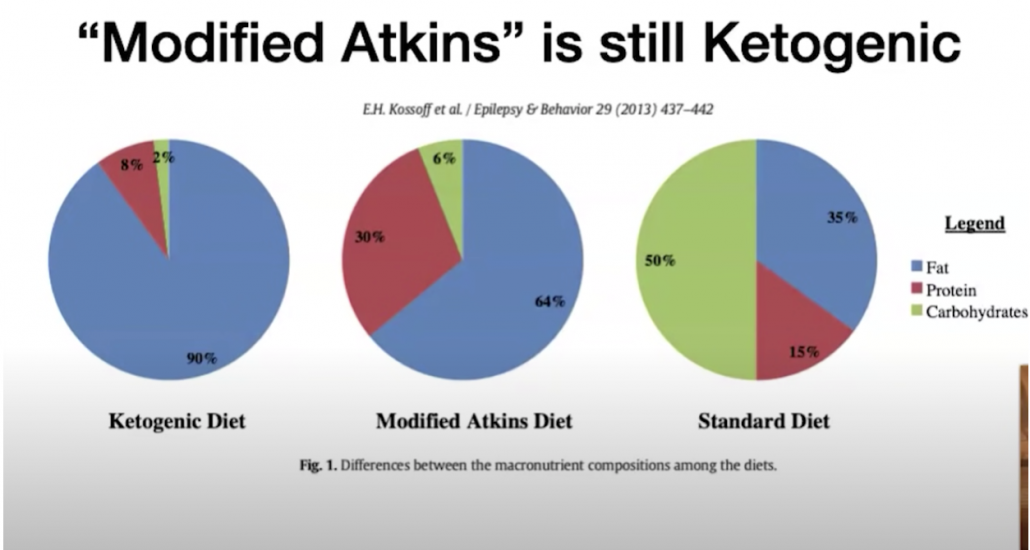

Many people are able to get seizure relief without limitations on protein, as long as they are eating a low-carb, high-fat diet. These findings support the fact that humans are evolved to produce ketones easily and not while starving.

We Need Fat

To generate ketones our bodies require more than low-carbohydrate levels. We need high levels of circulating fat.

If you’re not ingesting fat, didn’t just ingest it, and don’t have much stored on your body, you won’t produce ketones. The more fat that you are carrying, the more ketogenic capacity you have.

The reason humans are so fat, is to support high levels of ketosis.

If you were lean like a chimp, you wouldn’t be able to support the energy requirements of the massive human brain between meals.

The Takeaway: Fat is Where It’s At!

O’Hearn concludes that the secret behind the rapid expansion and cognitive power of the human brain starts with the supply of fat our ancestors derived from first scavenging fatty bone meats, and then hunting large fatty mammals.

Seeking and consuming fat became so central to the behavior of early humans that our species was able to drop its reliance on fiber. This shift to prioritizing dietary fat is evident in our genetic inability to replace fiber with protein for energy, and the fact that carbohydrate sources were limited and unreliable.

For the human species to make the transition to a larger brain we developed the ability to store fat, create ketones, and use them to fuel our brains and bodies, not just under starvation conditions but under mundane non-starving conditions.